|

Visitor:

2974683

| Incoming:

2/1/2026

at:

6:14:24 AM

Online Now : 1

|

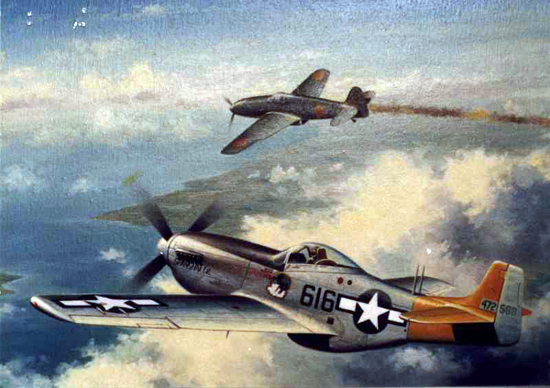

The 462nd was born in October 1944 as a child of the newly activated 506th Fighter Group and began training immediately with the North American P-51 Mustang for long-range escort duty.

Group photo of the Officers, taken on Iwo Jima, August 20, 1945

(missing from photo: Allen Colley, Leonard Dietz, and William Ebersole

|

|

Constituted in Oct 1944 at Lakeland Army Airfield in Florida, the 462nd was one of the cornerstone units in the 506th Fighter Group. Major Tom DeJarnette commanded the squadron for V.L.R. (click V.L.R. for explanation - also an extended story is here) very long range escort operations. DeJarnette was a veteran of early Southwest Pacific air action, serving as an A-24 pilot in New Guinea.

Activation 21 October 1944 to November 30, 1944

The history of the Squadron begins with its date of activation, 21st October 1944, by a General Order from the VII Fighter Command Headquarters.

The order established the sources from which the Officer had enlisted personnel was to be drawn. The order provided the 462nd Fighter Squadron with sixty-three officers and two hundred and forty-nine Enlisted men. The Officer Personnel was drawn mainly from the III Fighter

Command while the Enlisted Personnel was recruited throughout the III Air Force.

Mission

A flight of four P-51D Mustangs returning home from a mission to Iwo Jima. (USAF)

The intended mission of the squadron is to organize & train for VLR missions in the combat theatre. In accordance with directives from the VII fighter Command, however, specific information has not been received. As the climax of our training approaches, our minds are directed to the day of our departure from this base. All training has been completed and the squadron is busy making all necessary preparations to clear this base. A permanent detail of men, under the direction of IX Morin, Personal Equipment Officer, has bean working overtime to complete all the packing and crating. Service and immunization records were rechecked to make sure that their status was correct and up to date. Squadron Quartermaster Supply is making the necessary adjustments in equipment and E. M. are urged to turn in all unnecessary equipment. The Orderly Room is stressing the importance of arranging personal affairs before leaving the States. Instructions have been given as to the correct procedure of writing mail so it will meet the necessary censorship regulations. Elimination of personal documents, such as driver’s licenses, etc, was also stressed. Practically all sections have cleared the line and turned in their equipment. Some are still in the process of clearing the base. All airplanes have been turned over to the best unit, where they will be dispatched to other fields. Three sections are making a report of survey on the equipment which has been lost in the last three months. Squadron Quartermaster Supply has a report totaling sixty dollars. Personal Equipment has a report of sixty and Technical Supply has a report of eighty-even dollars.

On 10 February 1945 orders were received to send the air detachment forward. Twenty-six (26) Officers and twenty-eight (28) Enlisted, were selected to fulfill the order and proceed to the port of embarkation. The air detachment was commanded by the Squadron Commanding Officer, Major De Jarnette. Capt Stuart B. Lumpkins, Operations Officer, assumed command of the Squadron (Ex 2), before departure of the air detachment a picture was taken of all the flying and ground Officers.

On 10 February 1945, the Squadron held a party for all Officers and Enlisted Men, which was a complete success. The party was held in the Florida State Guard Armory in Lakeland, Florida.

During this month the Squadron had only one change in key personnel, Lt Delaronde, Squadron Adjutant, was replaced by Lt. Lillard.

The Squadron received official confirmation of its insignia from Headquarters Army Air Forces. The design of the insignia is authorized as follows: On light Turquoise blue disc, border yellow, a prancing, black thoroughbred horse with a white face and shanks, reared on a light turquoise blue cloud formation, edged dark blue in front of jagged red lightning flash striking from sinister chief toward dexter base.

The Lakeland A.A.F. " Bombshell * The base newspaper, has constantly promoted the Squadron capabilities by publishing reports of our outstanding pilots. This month our Commanding Officer, Major De Jarnette, and Lt. Willis, one of our pilots, both veterans of several missions in combat theaters, were selected as subjects in articles published on 9th and 15th.

|

|

| |

use slide bar to zoom + or - |

During this month the Squadron promoted several of its Enlisted Men. The flight detachment departed San Francisco, California, on the U.S. CVE #68 on 28 February 1945- Arrived Pearl Harbor, T.H., 6 March 1945 Departed there 7 March 1945- Arrived Guam 17 March 1945- Departed there for Tinian- Arriving 23 March 1945. M.S Bloemfontein was loaded with of the 462nd Fighter Squadron by March 16 1945- left on that date from pier #39 Seattle Washington. The ground Echelon arrived Bellows Field, Oahu T.H. A.P.O #951 A, on 23 March 1945 & departed that yield on 26 March 1945. On March 1 1945 there were 64 Officers and 256 Enlisted Men on 31 March there were 65 Officers and 254 Enlisted men. On March 1 1945 the Squadron had 26 P-51D’s.

On the first of march, the Squadron received orders to proceed to its staging area (2x-2) The Last days at Lakeland Army Air Field were spent in making the necessary preparations to entrain for the trip to Fort Lawton, Seattle Washington. The facilities of the port of Seattle were going to be used to embark the Unit toward its combat area. The train left Lakeland Army Airfield at four o’clock in the afternoon, 5 March 1945. The Unit arrived at Fort Lawton on the morning of the tenth of March and was immediately assigned to the casual area. Almost immediately the complicated process of clearing a unit for overseas began. The Unit was released from assignment to the 7th Fighter Command. The men were passed through a screening process, a physical and financial check-up was made. Chemical warfare lectures delivered, new gas mask and anti-chemicals protectives issued. All the men were urged any arrangement deemed necessary to enable their families and relatives to have clear-cut understanding of their individual financial allocations. The unit was alerted on the fifteenth of March, and proceeded next morning to the Port of Seattle pier #39. Men and materials were loaded on the M.S. Bloenfontein. This boat is of Dutch registry, with a Dutch merchant crew, and an American Navy armed guard. The ship weighed anchore at 15,13 hours of the afternoon of March 16 1945, and began to cruise over the Pudget Sound toward open seas. The ship made the run from Seattle to Honolulu T.H. in seven days of tempestuous sailing. It arrived at that port early in the morning of the twenty-third of March. There the Unit proceeded to disembark, to permit ship repairs and reloading.

The history that covers this month night be divided up into 2 parts. One that covers the movement of the air echelon up to the time of arrival to Tinian (MAP), in the Marianas group, the information concerning this section of our Squadron, is rather succinct in content, because lack of adequate records and availability of a correspondent. The other describes the movement of the Squadron in its trek from Seattle to Iwo Jima in the Volcano Group.

The air detachment departed Lakeland Amy Airfield, Lakeland Florida on the sixteenth of February 1945. The trip lasted five days and arrival was made at Camp Stoneman, Pittsburg California, in the San Francisco Bay area, February twenty-first 1945.

Its strength consisted of twenty-six Officers & twenty-eight Enlisted Men. Upon arrival, the group went through the routine that marks the processing of any unit that is going to a combat area. Clothing and physical check-up was made, chemical warfare indoctrination took place, and a final financial adjustment accomplished.

The stay in Camp Stoneman lasted eight days, in which the passes were issued to airman, thus giving them the opportunity of bidding farewell to the United States,

The departure took place the night of the twenty-eight (embarkation was made from the naval pier located at Alameda, also on the San Francisco Bay, on the USS Carrier Kalinin Bay on whose deck deployed the airplanes allocated to our group.

There were a total of seventy-nine (79) P-51’s. After eight days of travel, during which the detachment went thru air and submarine drills which characterize life on board ship. The carrier arrived at Pearl Harbor, at pier #12. There next to the carrier Saratoga, badly marked by scars of war, our group received the first impression of the effect of war on men and material.

After a day at Pearl Harbor, the ship pulled anchors and started its cruise to Guam (MAP) (Satellite View) arriving there on March sixteenth, where the air attachment disembarked. In Guam (MAP) (Satellite View) they were assigned to the Oroti naval Airfield, where they began to "unpickle”, put brakes on, and change spark plugs which had been damaged by cinders coming out of the smoke stack of the carrier. After three days of hard work seven of the airplanes were ready for the first test flight. Gradually all of the twenty-six (26) aircraft assigned to our Squadron were in flying condition and the Unit was ready for the next lap to Tinian. This time by air.

The ground crews left Guam partly by air, the balance proceeded aboard the USS Navy transport Stanton. Once in Tinian the detachment was directed to use for their testing and first Combat Air Patrol, the Tinian West Airfield, strip number 4.

The Tinian interlude lasted a month and ten days, the first Combat Air Patrol was flown on the twenty-nine of March. During this time the detachment had two accidents. Fortunately neither one of these mishaps resulted in fatalities to our unit. The attachment was commanded by Major Thomas De Jarnette, Commanding Officer of the 462nd Ftr Squadron.

Up to the thirty-first the Unit’s strength as twenty-six {36) officers, twenty-eight (28) Enlisted men. The total of combat time to this date was fifty-two {52) Hours and forty minutes.

The Mustangs their pilots arrived at Iwo Jima on 11 May. There they suffered their first casualty as Lt. Roland Carter crashed and was killed at North Field.

After some preliminary missions to Chichi-jima (Satellite) the 462nd conducted it's first long range mission to Honshu on 28 May 1945. Although they had trained for the escort role, this first effort was a low level strike at the airfields near Kasumigaura. The unit made a credible showing destroying many parked Japanese aircraft. However, they lost Capt. Kensley M Miller to flak over Imba Airdome. Miller was a veteran of a previous tour of combat in the Mediterranean flying P-40's with the 76th Fighter Group.

The next VLR mission on 1 June 1945 was an unparalleled disaster for the 462nd Squadron, the 506th Fighter Group and the entire Seventh Fighter Command. Along with the 15th & 21st Fighter Groups the 506th ran into a severe weather front in route to Osaka (MAP)(Satellite) . On that fateful day 27 Mustangs were lost and eventually 24 pilots would be listed as "missing in action." The 462nd lost three of it's own: Lawrence Smith, Gale Loomis and Archie Ridley. Capt. Ed Crenshaw, a staff officer of the 506th , flying a 462nd aircraft also failed to return.

As it was, the 1 June escort mission to Osaka was tragic. Originally scheduled for 31 May and cancelled because of unfavorable weather, 20 aircraft of the 462nd were airborne at 0745. At a point approximately 31 degrees North and 420 miles on course from Iwo, a weather front was encountered. The full story of what happened in the hours following the breasting of the front can never be known, but certain facts are remembered vividly. Upon reaching the front the navigator B-29’s executed a 360 degree turn as did the accompanying fighters. At this time radio conversations were garbled by an unwarranted maximum of discussion. Captain Lumpkins, leading the 462nd , heard a report on “Nan” channel, “Oranges are sour”. Unidentified remarks such as, “It is clear at our angels plus one”, and, “It is clear underneath”, were heard by many pilots. The front was entered at from 10,000 to 11,000 feet. It was soon apparent that the front was solid from the deck to the highest operational altitude. The 506th , under the leadership of Lt Col Scandrett, became completely disorganized. To add to the confusion in the impossible weather, the proximity of the 15th and 21st Fighter Groups gave cause for alarm. With all pilots flying on instruments and with visibility almost non-existent, it was inevitable that radio communications would become snarled by the many pleas for directional help. So bad was the weather that it was almost impossible for a pilot to keep contact with his wing man. P-51’s churned around in the “soup”, climbing, diving, spinning and even flying inverted, with no organization even as to direction. It was an “everyman for himself” proposition and some very good pilots were unable to survive the melee. 3 of the squadron pilots got through to the target by following a B-29. They returned to Iwo by following the ship very closely on the return route. The first general knowledge of the catastrophe reached Iwo when the first of the fortunate ships landed about 1300. The “sweating out” of pilots became a grueling ordeal. One accident was known to have occurred, a mid-air collision by the ships of Captain Crenshaw, a Group pilot flying a 462nd airplane, and 1st Lt. McClure. Damage to the tail section of Captain Crenshaw’s plane forced him to bail out at sea. Lt. McClure made base safely in spite of damage to the propeller of his ship. The passing of successive hours diminished hope for the return of all pilots. More than a few arrived with but a thimbleful of gasoline. After a definite maximum time during which all gasoline would have been expended, it was necessary to face the grim task of counting the missing of the squadron. These were Captain Crenshaw, a Group pilot flying a squadron aircraft, Captain Lawrence S. Smith, 0-665237, 1st Lt. Gale L. Loomis, 0-666404, and 1st Lt. Archie C. Ridley, 0-795639. Hope was high, however, for the eventual rescue of these men. Anxiety increased with the days lengthening into weeks as air-sea rescue facilities failed to find any trace of the pilots. Very persistent bad weather hampered the work of search, and caused the loss of one search plane engaged in the work of rescue. After a proper lapse of time the Bombers, Lt. Col Brown’s flight and 1st Lt Zagorsky’s flight down on the Jap from 20,000 feet. Most of the 8 aircraft of the 2 flights got in a burst and the Jap went down in flames. All 20 aircraft of the 462nd returned to base without further incident.

The following day 20 aircraft of the squadron took off on a projected strike against Meiji and Hamamatsu airfields on Honshu. 60 miles from Iwo a weather front extending from the deck to 28,000 feet was encountered and all aircraft returned safely to base, as this front was virtually impassable.

Lt. Virgil Newby, was downed on 8 July 1945 northwest of Tokyo and survived as a POW despite some mistreatment.

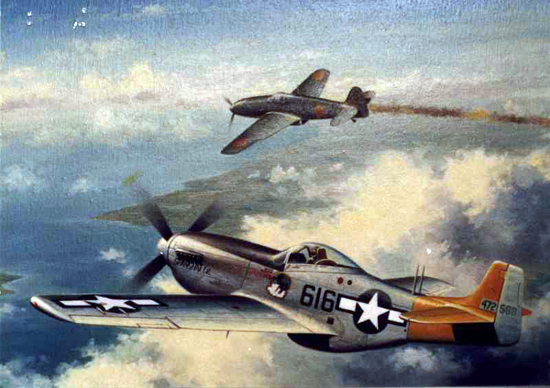

On the 10th of June, 22 aircraft of the 462nd completed an escort mission to the Tokyo area, the squadron providing our bombers with top cover. A Japanese squadron of Tonys, lying in wait for the bombers, was engaged by the 462nd . Major DeJarnette, Captain Lee, Lts Bash and Rosebrough each scored one aerial kill with no loss to our squadron. The 506th Group total was 10 enemy aircraft destroyed, 4 probably destroyed and 2 damaged. The squadron and group record was good, but the following day in a critique by Major DeJarnette, the mission leader, the “poor air discipline” was stressed and recommendations made to prevent a repetition. The Major noted that squadrons flew too close to one another, pilots were too individualistic and not watchful enough, and that wing men were not attentive enough to their leader’s flying.

Aerial encounters with the Japanese would be few & far between as the 462nd Squadron went more often to low level attacks on enemy airfields. Despite the dangerous nature of these operations the squadron lost only 2 pilots.

On 11 June thirteen ships of the 462nd bombed and strafed Radio Stations #6 and #7 at Chichi Jima. 16 bombs, 8 instantaneous and 8 delay-type, were unobserved as to results obtained. The following day a change in policy regarding Bonin missions was announced. A VII Fighter Command teletype gave each fighter group permission to dispatch “training missions: to the Bonin's as determined by each group commanding officer. On the 16th , consequently, 12 ships of the 462nd attacked Radio Stations #5 and #6 on Chichi Jima. For the first time in the history of the group 5 inch rockets were employed. Each of the 2 rocket craft carried 6 rockets apiece. The mission was successful and all aircraft returned safely to base.

On the following day the squadron loaned 2 of its rocket ships to the 458th which tried a similar attack on Chichi Jima. On the 19th the scheduled strafing mission against Meiji and Hamamatsu airfields was turned back by a weather front 250 miles on course from Iwo.

The following day Lt. James Roseborough bailed out of his damaged aircraft but apparently struck the tail and fell to his death.

Many 462nd pilots went down and were rescued and several carried battle damage back to Iwo Jima. Incredibly, their final causality would be over Chichi Jima. Lt. Albert Markin's plane exploded over the isolated island on 13 July 1945.

Japanese aircraft became increasingly hard to locate on the airfields, so it was with some surprise that the 462nd Squadron found itself being intercepted and engaged by Japanese fighters on 16 July (read here) near Nagoya (MAP). Turning into air attackers, the 462nd lost none and claimed three victories and three damaged.

The 462nd last encounter with the enemy aircraft was near Osaka (MAP) on 19 July when two Japanese fighters were downed.

Once again on 23 June the 462nd struck the enemy a solid blow. 20 aircraft of the squadron were dispatched to strafe Hyakurigahara airfield in the Mito area. An unusually high percentage of ships aborted, 7 in number, and 1 failed to take off. The 12 pilots who did complete the mission obtained excellent results. The mission was poor in the early part of its execution however. Rendezvous with navigational B-29’s over Kita Iwo Jima was delayed due to a confusion of orders, the B-29’s waiting on the west of Kita and the fighters waiting on the east of it. The 506th Group was delivered at a DP 10 miles further north on the coast line than called for in the field orders. To make a perfect day of snafu operation the B-29 leading the 462nd came very close to being hit by flak. Once over the target the 462nd was deadly, racking up a score of 5 enemy aircraft destroyed, 6 probably destroyed, and 4 damaged, all on the ground. 2nd Lt. Buzze set the pace with 2 Tojos destroyed. 6 types of enemy aircraft were observed: Georges, Nicks, Tojos, Tonys, Popeye,and Zekes.

462nd FIGHTER SQUADRON (SE)506TH FIGHTER GROUP (SE)APO 86

VII FIGHTER COMMAND

ARMY AIR FORCES, PACIFIC OCEAN AREAS

&

TWENTIETH AIR FORCE

- Negative

- Missing in Action: 1st Lt Virgil D. Nowby, 0-75223

Lt Newby bailed out successfully over the Empire on the

VLR mission of 8 July 1945.

Killed in Action: 1st Lt James E. Rosebrough, 0-756713

2nd Lt. Albert C. Marklin, 0-2067022

Lt Rosenbrough bailed out at sea on 9 July 1945. In so doing he apparently hit the horizontal stabilizer and lost consciousness. The pilot was last seen falling, chute unopened, at 2,000 feet.

Lt Marklin’s plane exploded over Chichi Jima on the mission of 13 July 1945.

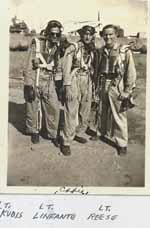

- Awards: One Soldiers Medal was awarded to Sgt Ferdinand H. Roth, 32392282, by the Commanding General, VIII Fighter Command, to the following pilots: Bahlhorn, Bash, Barcaw, Brenner, Buzze, Colley, Comfort, Cornett, Crowley, Dias, Dietz, Dingee, Ebersole, Findley, Freeman, Hiltz, Howard, Kincaid, Kubis, Linfante, Lumpkins, McFarlane, McNall, Millner, Posta, Rice, Seale, Stewart, Treasy, Wolfe and Zagorsky.

One Second Oak Leaf Cluster to the Air Medal was awarded Major De Jarnette by the Commanding General, VII Fighter Command.

- Strength, 1 July 1945, 68 Officers, 252 EM

Strength, 15 August 1945, 60 officers, 255 EM

6. Planes on hand, 1 July 1945, 32 P-51D’s

Planes on hand, 15 August 1945: 27 P-51D’s

7. Losses: Six (6) P-51D’s as follows:

8 July 1945-F/O Freeman bailed out successfully at Rally Point on VLR mission

8 July 1945-Lt Newby, Missing in Action

9 July 1945-Lt Rosenbrough, Killed in Action

13 July 1945-Lt Marklin, Killed in Action

13 July 1945-Lt Seale bailed out successfully at sea on return from Chichi misstion

30 July 1945-Lt Brenner bailed out successfully 4 miles from Iwo on VLR return.

UNIT HISTORY

462nd Fighter Squadron (SE)

506th Fighter Group (SE)

APO #86

VII Fighter Command: Army Air Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas: Twentieth Air Force

1 July 1945 through 15 August 1945

COMBAT OPERATIONS

Between 1 July 1945 and 15 August 1945 the 462nd Fighter Squadron flew often and well. During the period pilots of the squadron logged 3,209 hours, 2,989 hours of which was combat time. VLR sorties were predominant, numbering 321, as compared with 234 CAP sorties and a piddling 20 SR sorties to the Bonin's. These long hours of over-water flying were not without reward. According to the findings of the 506th Claims Board, 2 enemy aircraft were destroyed in the air over the Empire, and 3 Jap planes were destroyed on the ground. 2 Nip ships were damaged in the air and 2 were damaged on the ground. Some claims submitted during the period are still pending decision by the board. The number of Japanese aircraft destroyed or damaged seems small, in fact it is small. However, it was necessarily so as the number of Japanese sighted progressively declined during the period.

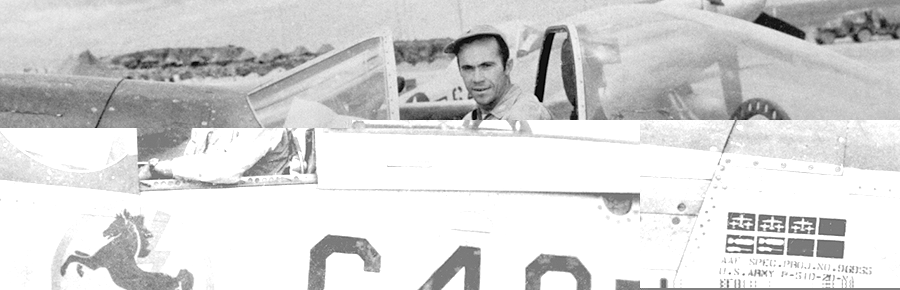

#604 Meatball pilot Lt. Bash and crew.

Proportionately the hurt to the enemy was as great during this period of flying as during previous months. In addition, shipping and rail facilities took heavy punishment from the guns and rockets of the organization. The size of naval vessels attacked ranged from small fishing craft to a small aircraft carrier and a light cruiser. Radar stations, radio stations, power stations, high tension lines, and small factories were hit often, especially in the latter part of the period, these targets being available when Japanese aircraft could not be discovered. Favorable weather sided greatly the progress of the squadron. 18 VLR missions were undertaken during the period, and only one of these was forced back from the Empire by unfavorable weather conditions. 3 missions to Chichi were successfully executed during the period, and only one of these was forced back from the Empire by unfavorable weather conditions. 3 missions to Chichi were successfully executed during the period. Hence weather caused abortive missions in less than 5% of cases whereas during the previous month this figure had been almost 8 times as great. The most intensive flying of the period occurred between 4 July and 9 July 5 VLR missions being flown in but 6 days. The first of these missions, on Independence Day, was an escort for 2 Navy B-24 photo ships which were to photograph Yokosuka Naval Base, one of Japan’s largest and most heavily defended naval installations. 24 aircraft were dispatched, 4 making early returns for various reasons, 5 providing sub cover with 15 going in over the target. 4 S/E Jap aircraft were sighted at a distance but could not be engaged due to the nature of the mission. All 462nd aircraft returned safely to base.

The following morning found 20 aircraft of the squadron airborne for a fighter strike at targets of opportunity in the shipping and dock area of Chiba Peninsula. 5 aircraft returned early with 15 successfully completing the mission. No enemy aircraft were sighted, though shipping was hit heavily, the squadron damaging 13 small naval craft.

On 6 July the squadron was again over the Empire for a strike at Yachimata airfield. 16 of the 20 aircraft taking off successfully completed the mission, inflicting damage to hangars and buildings on the airfield. South of Miyakawe several small fishing craft were left smoking. 12 rockets were fired during the mission. No enemy aircraft were sighted by squadron pilots at any time. A new defensive measure of the enemy was discovered above Yachimata airfield. About 25 to 30 red kites approximately 2’ x 4’ at 150 to 200 feet altitude were seen by pilots of the 462nd. Lt Kincaid’s plane suffered damage to the right outboard gun by machine gun fire, damage to the aileron by flak burst and damage to the leading edge of the wing by small arms fire. F/O Wolfes plane took small arms hits in the leading edge of the left wing.

On 8 July the 462nd participated in a fighter strike against Tokorazawa airfield and Irumasawa airfield. Of 20 aircraft dispatched only 18 returned safely to base.

1st Lt Virgil D. Newby, 0-752331, was forced to bail out south of the town of Denohara. Lt Newby’s chute opened over an apparently isolated area. This pilot was on his first VLR mission, having joined the squadron less than a week previously. Just what difficulty caused the pilot to jump was purely conjectural. Everyone hoped fervently that the downed pilot would not meet the fate of some of Doolittle’s flyers who bailed out over Japan in 1942. F/O Freeman was the second 462nd pilot forced to bail out on this mission. At 10,000 feet as he was passing over the coastline en route to the RP three bursts of AA fire bracketed his plane. The cockpit immediately began to fill with smoke and the engine commenced running rough. The canopy fogged up, which necessitated his rolling it back. Freeman honed in on the B29 navigator and after rendezvous was effected, started for base. 15 minutes after being hit the engine started to burn and he knew he would have to bail out. He called the B-29 for the location of the nearest “life guard” and upon getting the course set out upon it. Soon he had to jump, going out the right side without mishap. For the last 30 feet he hung to the parachute just by his hands, having previously unbuckled the chute. After inflating his dinghy he broke out his dye marker and waited. Soon the 3 circling P-51’s of the 462nd were replaced by a PB4Y Dumbo. 2 hours later the life guard submarine “Aspero” took the pilot aboard. 10 days later he was transferred to another submarine, landing at Guam 16 days after his bail-out. He sustained only minor injury from burns, using some of the boric acid from his C-1 vest to treat same after boarding his dinghy.

Lt. Rice in Funny Face in formation with F/O Freeman in Idas Imp

[credit: Ed Balhourn Collection]

During the course of the mission no enemy aircraft were seen at the target or on the ground. However installations on Tokorazawa were strafed. Later rockets and machine gun fire from the 462nd raised merry old hell with 7 electric power stations, one electric train, a truck, and 3 steam shovels. The last attack of the day was made on 2 factories. The planes of Lt. Brenner and Lt Dietz bore battle scars upon return. The former had a hydraulic line severed in the tail section and a machine gun hole in the flap of the left wing. The latter had 2 small holes in the canopy, caused by small arms fire. A new defensive technique was discovered as a result of this mission. Electrically controlled land mines were detonated north of the revetment area of Tokorazawa airfield, the Japs apparently hoping to use these mines effectively against low flying aircraft.

The following day, 9 July, the Mustangs of the 462nd took off for a strike against Hamamatsu A/F. 23 planes took off, 4 of these were early returns. 3 ships flew sub cover and 16 ships went in over the target area. One of these did not get back to Iwo as the plane crashed into the sea. 1st Lt James E. Rosebrough, 0-756713, bailed out, apparently unsuccessfully. Upon leaving the target area for the return to the RP, Lt Rosebrough’s ship probably developed an oil leak, as white smoke was seen coming from the first 3 exhaust ports of his engine. At 10,000 feet and near the RP the pilot announced on his radio, ”This is it!” and went out on the right side of his ship. He apparently was thrown into the horizontal stabilizer as he fell away from the airplane. With chute unopened, he was last seen falling at 2,000 feet where he entered a dense cloud bank. Lts Dingee and Ebersole circled in the area surrounding the plane’s oil slick for 30 minutes, but sighted no trace of the pilot. 2 Playmates subsequently took over the search which proved unsuccessful. Aside from this tragedy the mission was successful. One Jap aircraft, a Pete, was sighted and damaged by Lts Rice and Comfort who were flying sub cover. Marshalling yards near the Toyokawa arsenal took heavy strafing and rocket attacks from the squadron flyers, no attempt being made to strafe the target airfield as only dummy aircraft were observed o that field.

Flying let up until 13 July when 6 aircraft of the squadron flew to Chichi Jima with 10 ships of the 457th. Of the 4 rocket ships going over the target, 2 were lost. 2nd Lt Albert C. Marklin, 0-2067022, was the M2 rocket ship. The#1 man who preceded him over the target pulled up to observe hits and noticed what appeared to be an aircraft or a large shiny object in a series of snap roll spins going down over the target and then striking the ground. Lt Col Brown and Captain Lee, flying as observers saw a single bleek puff of smoke similar to heavy flak at about 8,000 feet where Lt Marklin’s plane might have been expected to be. A few seconds later both saw shiny looking objects falling to the ground, which appeared to be wing tanks or wheel fairings. Upon return to base 4 aircraft were dispatched to search for Lt Marklin but all efforts proved unavailing. Lt Seale was unable to fire his rockets at Chichi installations but did successfully jettison them on Kita while returning to base. A coolant leak developed and flashes of fire began to come from the engine. Lt Seale bailed out successfully, his chute opening at approximately 3,500 feet. Very shortly after boarding his dinghy he was picked up by a naval craft and was returned to Iwo.

The 462nd seemed to be hitting a bad run of luck. On the last 3 missions, 3 pilots had been lost, 2 more had been forced to bail out and 5 planes had been lost. The tide turned at this point however, and throughout the remainder of the period no casualties were suffered by the squadron although one more aircraft was lost.

On 14 July the 462nd put 20 planes in the air for a strike at airfields in the Nagoya area. An impossible weather front en route to the target was encountered and all planes returned safely to base.

Three Mustangs on CAP over Iwo Jima. Pilots are Ed Linfante in #628, Ed Bahlhorn in Meatball, and Jesse Sabin in Little Joe. CAP patrol over Iwo 2nd Lt. Ed Linfante in a Josephine (containing inflatable raft) configured P-51. Pilots were rotated in flying the Josephine on CAP. CAP was confined to a radius of approximately 50 miles around Iwo. The tank was supposed to be dropped at very low altitude (for accurate targeting) to a pilot or other downed person in the water (B-29 crewman, etc.) who may not have had his own inflatable raft. I'm not sure it was ever employed. We always carried an annoying, but necessary, dinghy hung below our butt as standard equipment. (Memoirs of 2nd Lt. Ed Linfante Pilot 462nd Squadron)

On 16 July the 20 ships of the squadron found it impossible to strafe airfields in the Nagoya area because of enemy interception. 10 to 13 enemy aircraft were slighted and attacked. Several aircraft were probably destroyed and 3 others damaged from the ensuing air fighting.

Chichi was hit by rockets and bombs on 18 July, 4 ships of the squadron going in for the attack. Damage from this operation was unobserved, but Colonel Harper, the group commander, who flew as an observer felt that more practice in dive bombing would be feasible. En route to Chichi the squadron ships had searched at Haha Jima for enemy shipping and had found none. A few hours later a similar mission to Chichi was executed, this again with undetermined results. 2 strikes in the same day was a new record for the 462nd.

The following day the yellow-tailed Mustangs of the 462nd left Iwo, 19 strong, for a strike against Itami, Nishinomiyo and Tambaichi airfields. 13 enemy aircraft were caught in the air and of these 2 were destroyed. Captain N. T. Miller shot down an “Oscar” in flames and Lts Buzze and Dietz shared a “Tojo”. Going to the deck the squadron strafed power lines and smoke stacks with good success. All ships returned safely to base.

On 22 July the targets of the strike were Takamatsu, Tokoshima, and Minato airfields. Aircraft could not be found on these fields and hence targets of opportunity were sought. Captain Lee and his wingman, Lt Treacy, discovered an “Emily” type flying boat on the Inland Sea and destroyed it. Severe damage on cargo vessel about 450 feet long was wrought. The squadron got tangled up with a Japanese aircraft carrier and a light cruiser in the Inland Sea and braved very heavy ack ack in attacking these. Results were mostly unobserved as wisdom dictated a fast leavetaking.

2 days later 21 aircraft of the squadron participated in the strike against Yaizu,Oi, and Hamamatsu airfields. No enemy aircraft were sighted on the target fields or in the air. Radar screens, radio stations, small cargo vessels and a lighthouse were strafed heavily by the squadron.

On 28 July 18 aircraft were sighted in the air or on the ground. Koga airfield installations were damaged as well as a radio station, a steam locomotive and freight cars, a power station, high tension towers, a bridge, and small coastal vessels. The radio station strafed was the largest radio station yet seen in the Empire by the squadron pilots.

A strike at Kakogawa in the Kobe area on 30 July netted similar results. No enemy aircraft were sighted in the air. Non-operational aircraft and dummy aircraft were sighted on the target airfields. Maintenance buildings and barracks were strafed with good results, before beginning the search for targets of opportunity. A small factory in a nearby area was set afire, and power lines came in for a severe machine-gunning. One aircraft was lost on this mission, heartbreakingly close to home. 4 miles west of Iwo, Lt Brenner’s ship ran out of gasoline, forcing him to jump. Little time elapsed between the successful bail-out and the rescue of the pilot. A second aircraft was miraculously saved from a similar plunge into the sea by the skill of Lt McFarlane. This pilot reached South Field just as his engine went out once and for all. His dead stick landing was a thing of beauty, and plane and pilot completely escaped injury.

The mission of 2 August bore out again the unwillingness or inability of the Japanese Air Force to enter combat with our American fighters. No enemy aircraft were seen at Itami airfield in the Osaka Area, nor were any sighted throughout the course of the mission. A marshalling yard was worked over, 1 steam locomotive being destroyed and a number of tank cars damaged. 2 factories near Himeji were strafed with good results. Along the coast 2 small boats were damaged by our low flying aircraft. All planes returned safely to base. It was noted upon landing that Lt. Hiltz had a close call, his plane having received a hit in the air scoop.

A sweep in the Tokyo area was carried out on 3 August, 20 aircraft of the 462nd taking part. “No enemy aircraft sighted” again went into the mission report.

The Odawara railroad yards bore the brunt of the day’s attack. An electric engine, freight cars, and a signal light were damaged. One steam engine was destroyed.; Several factories nearby were damaged and coastwide luggers were shot up. En route home the 462nd spotted what appeared to be 4 small aircraft carriers, 1 battleship, and 3 destroyers of the Imperial Fleet, and these were given a wide berth. Damage to 2 ships was discovered on landing. The left wing of Lt Brenner’s ship had been hit by a small caliber bullet and one propeller blade was damaged near the hub. Damage to Lt McNall’s ship was much greater as an explosive shell had torn a gaping hole in the right horizontal fin. In addition machine gun bullets had penetrated the vertical stabilizer.

On 5 August a sweep in the Tokyo area, with special attention

to Tachikawa airfield, was planned. The story was the same; no enemy aircraft rose to challenge our fighters and were nowhere to be seen on the ground. One steam locomotive and cars were strafed as well as a power station and high voltage towers. In the attack on a train at Matsuda Lt Miller’s ship was hit in the windshield, in the right wing between the guns and the landing gear, in the prop spinner, and in the left horizontal stabilizer.

On 7 August the squadron took off on an escort mission to the Tokyo area, with a strike at Atsugi airfield as an alternate possibility. No operational enemy aircraft were seen during the course of the mission. At Odawara 2 fishing boats were strafed and damaged. At Manazura 1 docked Sugar Dog was set ablaze. South of Sekimoto a factory was strafed and firs were started. A steam engine and 5 to 10 freight cars in the yard at Sekimoto were damaged and power lines were hit. Returning to Matsuda which had been hit on the previous mission, an attack was made on the railroad yards and the depot, fires breaking out in the depot. One steam locomotive was damaged in the yard. At Kama Oi a railroad station and 4 flat cars were damaged.

The pilots taking off on 10 August were cheered by excellent news of the past few days. The atomic bomb smash at Hiroshima on 6 August and Russia’s entry into the war against Japan had boosted morale to a new high. As the mission was soley escort to the Tokyo the 3 enemy aircraft sighted in the air and at a distance and the 8 seen on the ground could not be attacked.

The last mission of the period and it was hoped of the war was flown 14 August during the time the Japanese Government was considering the Allied counter-offer of surrender terms. This mission was an escort to the Osaka-Kobe area. No enemy aircraft could be found in the blue or on the ground.

The combat flying of the 462nd Fighter Squadron ended quietly on 15 August 1945 at 0900, when the radio carried the voice of President Truman announcing Japan’s capitulation. During the few months of combat flying the 462nd had done very well indeed. The Squadron ending the war with a total of ten aerial victories.

14 Distinguished Flying Crosses were awarded by the Commanding Officer, VII Fighter Command, to the following pilots; Bash, Diaz, Hiltz, McNall, Stewart, Willis, Lumpkins, Ebersole, Howard, Treacy, Wedum, Colley, Dingee and Jutras.

1 Oak Leaf Cluster to the Distinguished Flying Gross was awarded to Major T.D. De Jarnette by the Commanding Officer, VII Fighter Command.

The Bronze Star Medal was awarded M/Sgt Wilburn A. Smith by the Commanding Officer, VII Fighter Command.

The Purple Heart was awarded F/O John E. Freeman by the Commanding Officer, VII Fighter Command, for burns received while bailing out on the return of a VLR mission.

2 Air Medals were awarded posthumously by the Commanding Officer, VII Fighter Command, to 1st Lt. James E. Rosebrough and F/O Albert C. Marklin.

17 First Oak Leaf Clusters to the Air Medal were awarded by the Commanding Officer, VII Fighter Command, to the following pilots Miller, Reese, Rosebrough (posthumously), Yield, Bahlhorn, Brenner, Cornett, Crowley, Diaz, Ebersole, Freeman, Gourley, Graham, Knapp, Podeswa, Sabin and Sullivan.

30 Second Oak Leaf Clusters to the Air Medal were awarded by the Commanding Officer, VII Fighter Command, to the following pilots: Freeman, Brenner, Rosebrough (posthumously), Kubis, Millner, Alee, Seale, Weld, Buzze, Comfort, Dingee, Gourley, Grant, Linfante, McFarlane, Meyer, Stewart, Wedum, Zagorsky, Bahlhorn, Colley, Crowley, Diaz, Ebersole, Graham, Hawks, Knapp, Sullivan, Lumpkins and Dietz.

|

|

|

Lt. Kubis, Linfante, Reese in flight gear ready for a mission. |

Lt. Rice flying in formation with F/O John Freeman in “Ida’s Imp.” (Marine Aerial photographer) |

Lts. Harley Meyer, Ed Linfante, Newt Millner, Harry Reese, and Bob Graham |

|

|

|

Corky-Belle of Auburn Lts. John Kubis and Ed Linfante with the crew of 638. Crew Chief is S/Sgt. James D. Sledz ans Asst. CC is S/Sgt. Eiland E. Helms. Other crewman is not identified. (From Ed Bahlhorn) |

Front: Lts. Robert Gourley and Frank Buzze. Back: Lts. Bernie Comfort, Jack Rice, Thomas McNall, and Harold Stewart. (From Ed Bahlhorn)

|

462nd Mustangs on the flightline.

(Official USAF photo) |

|

|

|

Capt. Lawrence S. Smith missing in action 1 June 1945 during horrific storm front encountered on way to Osaka, Japan |

Capt. JJ Grant sitting on the wing of his P-51 after a long mission to Japan |

Group of pilots in front of Ed Bahlhorn’s “Meatball.” Front row: Lts. Treacy, Hawks, F/O Knapp, Lts. McNall, and Bahlhorn. Standing: Lt. Dingee and Capt. Findley |

|

|

|

Marshall, Nix, Collier, Dietz

L to R - Lt. George Nelson, Lt. John Wedum, Capt. Norman Miller, Lt. E. F. Balhourn, knelling Lt. Larry Hawks - June 1945 |

CAP patrol over Iwo 2nd Lt. Ed Linfante in a Josephine (click here for explanation) configured P-51. "Pilots were rotated in flying the Josephine on CAP. CAP was confined to a radius of approximately 50 miles around Iwo. The tank was supposed to be dropped at very low altitude (for accurate targeting) to a pilot or other downed person in the water (B-29 crewman, etc.) who may not have had his own inflatable raft. I'm not sure it was ever employed. We always carried an annoying, but necessary, dinghy hung below our butt as standard equipment."

Memoirs of 2nd Lt. Ed Linfante Pilot 462nd Squadron

»ED Linfante Photo Gallery« |

#640, "Shawnee Princess", a 462nd Mustang. Frank Seale the pilot in this plane. Frank, flying another plane had to bail out on a Chichi Jima mission (credit: Balhorn)

"The guy in front of me (Lt. Marklin a new replacement pilot to our Squadron, it was his 1st mission) blew up and shrapnel went into my engine - I think it tore up my coolant line - I started overheating about 20 minutes later and had to go for a swim".

Pilot Frank Seale |

|

Crew Chief Technical Sergeant Daniel A. Porcellini of the 462nd Fighter Squadron. As a crew chief for the plane "sniffles" in wich Captain Lee flew, he was awarded two bronze stars, one for having his planes ready for twenty consecutive missions with out an abort and one for his bravery on Iwo Jima.

|

Standing L to R - Lt. Gordon Dingee, Capt. John Findley, Lt. Newt Millner, Seated - Lt. Steve Treacy, Lt. Larry Hawks, F/O Emery Knapp, Lt. Tom McNall, Lt. Ed Balhourn June 1945 |

|

|

Lt. Bill Ebersole Collection |

|

|

|

| |

Captain Lee |

Lt. Bash 616 |

Lest We Forget

Killed or Missing In Action

1st Lt. R.E. Carter

1st Lt. Loomis - 1 June 1945

Capt. K.M. Miller - 28 May 1945

1st Lt. Ridley - 1 June 1945

1st Lt. Roseborough - 9 July 1945

2nd Lt. Marklin - 13 July 1945

Capt. Lawrence Smith - 1 June 1945

Arrival time: 2/1/2026 at: 6:14:24 AM

top

|