- HOME

- 506TH STORY

- SQUADRONS

- PILOTS

- IWO TO JAPAN

- MAY/JUNE MISSIONS

- MAY/JUNE MISSIONS

- MAY 28th | TOKYO AREA AIRFIELDS

- JUNE 1st | BLACK FRIDAY 25 Pilots Lost

- JUNE 7th | OSAKA | 138 P-51s of 15th, 21st and 506th Groups

- JUNE 8th | NAGOYA AREA

- JUNE 9th | NAGOYA AREA

- JUNE 10th | TOKYO AREA

- JUNE 11th | TOKYO AREA

- JUNE 14th | BONIN ISLANDS

- JUNE 15th | OSAKA AREA

- JUNE 19th | TOKYO AREA AIRFIELDS

- JUNE 23rd | TOKYO AREA

- JULY MISSIONS

- JULY MISSIONS

- JULY 1st | TOKYO AREA five enemy aircraft destroyed, seven damaged

- JULY 3rd | DEATH AT CHI CHI

- JULY 4th | TOKYO AIRFIELDS

- JULY 5th | TOKYO AIRFIELDS

- JULY 6th | TOKYO AIRFIELDS

- JULY 7th | WEATHER ABORT

- JULY 8th | TOKYO AIRFIELDS

- JULY 9th | TOKYO AIRFIELDS Sixteen enemy aircraft destroyed, five probably destroyed and eleven damaged

- JULY 14th | NAGOYA AIRFIELDS

- JULY 15th | NAGOYA AIRFIELDS

- JULY 16th | CAPT BENBOW LOST/AUST DOWNS 3

- JULY 19th | NAGOYA/OSAKA

- JULY 20th | NAGOYA AREA

- JULY 22nd | OSAKA/NORTHEAST SHIKOKU

- JULY 24th | NAGOYA AREA

- JULY 28th | NAGITA AREA

- JULY 30 | KOBE/OSAKA

- AUG MISSIONS

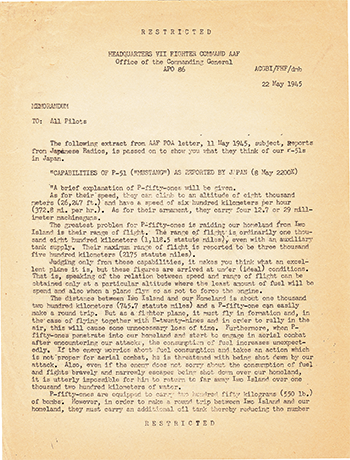

506th Fighter Group - Iwo to Japan

Their heritage began at Pearl Harbor

Missions to Japan |

|||

May/June

|

June

|

July/August

|

|

|

|

|

Number 46 (FC Mission #254) 5 August 45

Mission: Two Group VLR Fighter Strike against airfields and military installations in the Tokyo area.

Results: Four enemy aircraft destroyed or damaged on the ground and enemy ground installations and shipping destroyed or heavily damaged. Our losses: Three Mustangs lost and two pilots missing

05 AUG Number 47 (FC Mission #255)

The crew for Capt. Evelyn Neff's P-51 Mustang of the 457th FS. From L to R: Sgt. Henry P Manns (asst. Crew Cheif), S/Sgt W.W. Guason (Crew Chief), Pfc. Henry W. Benoit (armorer). Neff was lost on the August 5 VLR mission to Tokyo, as on a low strafing run, his wing hit the water. The Mustang's wing broke off and the aircraft hit the water and exploded.

Target areas were assigned in the same manner as on the previous mission. One squadron of the 506th Group hit ground targets, including the railroad yards at Ninomiya and Odawara, while a second squadron hit railroad yards and a station at Matsuda and an industrial installation south of Sikimoto. Both squadrons failed to find aircraft on fields in the area. Shipping was strafed enroute to the Rally Point during which time one P-51 and pilot were lost. The 21st Group rocketed and strafed Katori airfield destroying or damaging four planes on the ground and damaging buildings and other installations on the fields. One pass was made at Kasumigaura airfield with undetermined results. One pilot was lost on the way home when his engine failed. He parachuted but was not picked up. Only one airborne enemy aircraft was sighted, an unidentified single-engine plane over Hiratsuka, which was too distant to attack.

Letters From Iwo Jima: The Air War: Aug 6th:

Letters From Iwo Jima: The Air War: Aug 6th:

Number 47 (FC Mission #255) 6 August 45

Mission: VLR Fighter Strike against airfields and military installations in the Tokyo area.

Results: One aircraft destroyed, three probably destroyed and twenty-one damaged on the ground.

Our losses: Six P-51s lost, five due to flak and a sixth due to operational failure.

Three of the pilots were rescued. Weather conditions again hampered operations. The 15th Group strafed and rocketed Sagami airfield, last resort target, with resultant damage to the hangar and building area on the west edge of the field. Targets of opportunity were strafed on retirement form the area. Flak was accurate in some sections and three planes were lost to this fire; one P-51 was lost operationally.

Squadrons of the 21st Group failed to attack primary targets due to cloud coverage in one instance and failure to find visible targets in another. One squadron attacked a secondary target, Kashiwa airfield, using a new system of attack in an effort to locate dispersed and camouflaged aircraft definitely known to be located in the near vicinity. The squadron assigned a section of the field and its environs to each of its flights with orders to make a thorough search of each area before attacking. Following this plan one pilot, circling the area northwest of Kashiwa, detected ten Tojos, five on each side of a road, parked nose to the road, under trees and heavily camouflaged. The planes were strafed and attacked but did not burn or explode indicating that tanks were empty. The planes of this group were lost to flak.Number 48 (FC Mission #257) 7 August 45. Mission: VLR Escort of B-29s over Nagoya or Tokyo with a Fighter Strike scheduled by one group in event the bombers did not appear at their Initial Point. Two groups were scheduled for this mission. One group was to escort a force of B-29s to Toyokawa, but if this target were to be found closed in, the bombers were to proceed to Yokosuka where the second fighter group was to take up the escort. If the bombers did not appear over the secondary target, this second fighter group was to strike airfields in the southwest Tokyo area.

The escort phase of the mission was routine with the bomber force hitting its primary target and the 15th Group escorting. One P-51 was lost operationally on the way to the rendezvous, but the pilot was rescued. When the bombers did not appear at the point of rendezvous over the secondary target, the Mustangs of the 506th Group continued on their alternate mission. Two squadrons investigated Sagami and Atsugi airfields with negative sightings. A variety of targets of opportunity was strafed and all planes of this group returned to base safely.

During the entire mission, no airborne enemy aircraft were sighted, despite the fact that weather conditions were favorable to interception with visibility unlimited. No friendly fighters were lost or damaged due to enemy action on this mission.

Number 49 (FC Mission #258) 8 August 45

Mission: Two group VLR Fighter Strike against airfields and facilities in the Osaka area by planes of the 414th and 21st Groups.

Losses: Six. Three P-51s lost due to flak.

Two pilots are missing and one pilot was picked up by an ASR submarine. Two additional planes went down for unknown reasons, and another went down due to lack of gasoline. Two pilots were rescued and one went in with his ship. Eleven friendly aircraft were damaged, five planes by flak and six when dropping 165 gallon wing tanks. No airborne enemy aircraft was sighted.

In a well known USAAF stock photo, 506th FG P-51 Mustangs await their turn for take off on another VLR mission to the island of Japan. Many plane numbers are visible, showing mostly 457th and 458th squadron aircraft. Note the mix of striped and solid colored tails.

Number 50 (FC Mission #259) 10 August 45

Mission: Two group VLR Escort of B-29s over the Tokyo area by the 15th and the 506th Groups.

Results: Six enemy aircraft destroyed, one probably destroyed and eleven damaged in the air.

Our losses: None.

One P-51 was damaged in release of wing tanks and another was hit by flak. Neither pilot was injured and the planes returned to base.

Lt. Francis Albrecht and his crew cheif stand beside his P-51 'Erma Lou', #514 of the 457th FS. The plane was named for Albrecht's wife and was shared with Lt. Chauncey Newcomb.

The last encounter with Japanese fighters came on 10 August, when the 15th and 506th FGs were assigned to escort B-29s to Tokyo.

But the enemy did not collapse immediately, so the 'Sun Setters' continued flying missions to Japan. After hitting airfields in the Tokyo area on 2, 3, 5 and 6 August, and losing eight pilots in the process, VII Fighter Command put up an escort mission to Tokogawa on 7 August and struck airfields at Osaka 24 hours later, losing three more pilots and six p- 51s to ground fire. In these six missions, just one enemy aircraft had been shot down.

Both the 15th and 506th Groups escorted the Superfortresses over the target. Twenty-eight Jap fighters were sighted on the mission, only three of which were aggressive towards the bombers. No unusual enemy tactics were noted and our planes maintained mutual support tactics with good results.

Among the seven victories credired ro the 'Sun Setters' was one to Maj 'Todd' J\1oore of the 45th FS, bringing the ace's victory total to 12, and rwo to Capt Abner Aust of the 457th FS, making him the 506th's only ace, and the last pilot of VII Fighter Command to tally five or more victories.

Number 51 (FC Mission #260) 14 August 45

Mission: VLR Fighter Strike against airfields and military installations in the Nagoya area and Escort of B-29s in the Osaka area.

All four fighter groups of the VII Fighter Command participated in this mission. The 15th with P-51s and the 414th with P-47s were assigned targets in the Nagoya area for Fighter Strikes, while the 21st and 506th Groups, both with P-51s, were designated as escort forces for the bombers.

The 414th was navigated to a point twenty miles southeast of the briefed landfall which caused some difficulty in locating the assigned target airfields. The primary target, Akenogahara airfield, was located, however, and was attacked as were targets of opportunity enroute to that field. The Owashi area was first strafed with resultant damage to warehouses, barracks, factories and some small shipping offshore. The group then proceeded to Akenogahara where the south dispersal area and shops were strafed. One Thunderbolt was abandoned at the Rally Point because of flak damage but the pilot was rescued.

The 15th Group damaged one Frank on Komaki airfield and attacked the marshalling yards west of the field. A general search of the area east of Nagoya was made and all worthwhile ground targets were strafed in a sweep which took the group south as far as Toyohashi airfield where one Sally was damaged. Three planes of the 15th Group were lost but two pilots were rescued. The escort phase of the mission was flown without incident and all planes of the escorting groups returned to base safely.

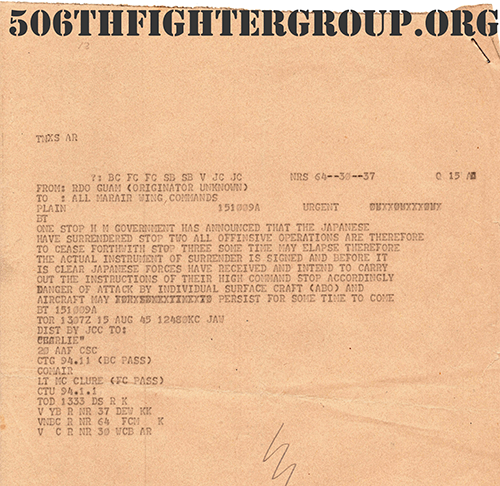

All four fighter groups headed for Japan on 14 August for what would be their last combat mission of the war. 1Lt J W 'Bill' Bradbury of the 72nd FS recalled that the mission was postponed for two days while surrender negotiations were underway before VII Fighter Command was finally ordered to fly. He recalled the mission;

'We arrived off the coast of Honshu and joined the bomber stream to escort them over their target. They dropped their bombs, and we went back out over the ocean to join our three (navigatot) B-29s. As we joined them and started flying back to Iwo Jima, one of the B-29s had picked up radio transmissions and came on the air saying, "Hey fellows, the war's over". I remember someone punching theit mike button and replying, "Well the Japs sure as hell don't know it". He was referring to all the flak that was put up over the target against the bombers. We took about threeand-a-half hours to fly back to Iwo Jima and landed. Sure enough, the war was over.'

As best can be determined 60 years after the fact, at the cessation of hostilities VII Fighter Command had run up a score of 452 Japanese aircraft destroyed in the air and on the ground. Countless other ground targets had also been attacked during strafing missions. VII Fighter Command had paid a high price for this success, however, as 130 Mustangs were lost and 121 men killed or captured, including the victims of the 26 March banzai raid. But not a single 'Sun Setter' would say the sacrifice was not worth the final reward of victory in the Pacific.

For the next two weeks flying was restricted to the local area around Iwo Jima, as everyone awaited word of the actual signing of the peace agreement. Then on 31 August the 'Sun Setters' were assigned a final VLR mission to Japan - a 'Display of Power' flight over Japan, led by Col Harper of the 506th FG. Few were eaget to risk another long haul over the Pacific, and sure enough one pilot, 1Lt William S Hetland of the 457th FS, experienced engine trouble over the target area. Fortunately, Hetland made a safe landing at Atsugi Airfield and returned to Iwo aboard a C-46.

On 2 September, Brig Gen 'Mickey' Moore boarded an LB-30 Liberator transport with orders reassigning him to the Pentagon. Within a week, the most veteran pilots and ground personnel began getting their tickets home as well. VII Fighter Command began shrinking rapidly, and in October pre-separation lectures were instituted for the men.

Late in the year, the headquarters was moved to Guam and redesignated the 20th FW. The 506th FG was deactivated in mid-November and its remaining personnel transferred to the 21st FG, while the 15th FG was transferred to Hawaii for deactivation. The 21st FG finally transferred to Saipan in the final weeks of 1945 and then moved to Guam, where it was redesignated the 23rd FG in October 1946.

Between 1952 and 1955, all three VLRgroups were again reactivated as USAF fighter wings. The 506th Tactical Fighter Wing was inactivated for good in 1959, however, although the other two - now the 15th Airbase Wing and the 21st Space Wing - continue to serve their nation as this book is written.

And what became of the stinky, depressing and dangerous island of Iwo Jima? American forces continued to serve on Iwo for many years after the armistice. Central Field, formerly home of the 21st FG, was maintained and expanded, while the other two runways were abandoned and allowed to be taken back by nature. American servicemen could still find the bones of Japanese soldiers in Iwo's caves into the early 1950s, and the Marine Corps occasionally used the island to conduct combat exercises. The US Coast Guard established a LORAN (Long Range Navigation) station there as well.

According to recently uncovered information, the US stored nuclear weapons on Iwo Jima (and Chichi Jima) from 1956 until 1966. Then in June 1968 the Bonin and Volcano islands were returned to Japan, becoming part of Ogasawara village in the Tokyo Metropolitan Prefecture. The Japanese Self Defence Force has used Iwo Jima as a patrol and rescue base ever since.

In 1995, the Japanese government allowed a small delegation of Americans to visit the island for a remembrance ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of the historic events that took place there during World War 2.

The final score which the 506th had tallied on the twenty-two effective VIR Missions run in the period 28 May to 14 August was as follows:

DESTROYED |

PROBABLES |

DAMAGE |

LOSSES |

Air : Ground |

Air : Ground |

Air : Ground |

Pilots : Planes |

39 : 22 |

11 : 11 |

33 : 96 |

20 : 29 |

This aircraft score, though, was not the only measure of the Group’s effectiveness. Our tally of rolling stock, power lines, and shipping which, due to the nature of the targets, cannot be as accurately estimated as the aircraft score, should be included in the record.

HEADQUARTERS TWENTIETH AIR FORCE APO 234, c/o Postmaster San Francisco, California GENERAL ORDERS 23 January 194-6 NO 13 SECTION XVII DISTINGUISHED UNIT CITATION

As authorized by Executive Order No9369 (Sec I WD, Bull 22, 1943), superseding Executive Order No 9075 (Sec III, WD, 1942) and under the:provisions of paragraph 2d (l), Section IV, Circular No 333, WD, 1943, and letter Headquarters United States Army Strategic Air Forces, file AG 200.6, subjects "Distinguished Unit Badge" dated 11 October 1945 and paragrpah 4 SectionI, General Orde s 1, Pacific Air Command, United States Army, 25 December 1945 (Classified), the following units are cited for outstanding performance of duty in action against the enemy; The 506th Fighter Group is cited for outstanding performance of duty in armed conflict with the enemy during the period 7 June 1945 to 10 June 1945. With exceptional valor and proud skill, this Group participated in two highly successful maximum effort very long range missions in escort of B-29s which had as their objective the destruction of two important industrial centers of Japan, Osaka and Tokyo. Despite the appalling loss of fifteen planes and twelve pilots on the preceding mission only six days before, and despite such adversity as the withering heat which billowed in on winds laden with Iwo Jima's volcanic ash, morale remained exceedingly high. The Group was more determined than ever, and the required number of planes was airborne on schedule on 7 June 1945 and again on 10 June 1945. Those intrepid fighter pilots flew vast distances over water to support the heavily laden bombers against some of the most fanatical and effective opposition ever mounted by the enemy. The opposition was intensified by the need for the bombers to fly these strikes at medium altitudes because of the problems occasioned by incendiary bomb ballistics and by the unpredictable and excessive winds at high altitudes. This tactical necessity subjected the aircraft to continuous attack from the largest concentrations of enemy fighters and anti-aircraft guns in the area. Hurling themselves through the accurate anti-aircraft fire, these intrepid pilots met the vicious enemy fighter attacks so skillfully that only one B-29 was lost to enemy action while eleven enemy airdraft were destroyed, four probably destroyed and two damaged. The success of these missions against two of the major industrial strongholds of Japanese war might was a fitting tribute not only to the coolness and skill of the gallant pilots of the Group, but also to the ground personnel working endless hours to keep the aircraft in the air although acutely short-handed and continuously improvising to overcome a shortage of tools, equipment and replacement parts. The conspicuous determination, unremitting devotion to duty and gallantry in the face of extremely adverse conditions and concentrated defenses of an aggressive and resolute foe displayed in the preparation and execution of these missions reflect the highest credit on the 506th Fighter Group and upon the United States Army Air Forces. |

ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION OF ESCORT AND STRAFING TACTICS

Escort Tactics:

The tactics followed daring the escort missions’ flown by the 506th adhered closely to the provisions of the VII Fighter Command Tactical Directive. The Group patrolled the bomber stream at a distance of 3000’ out and 30001 above the level of the B-29’s. The formation employed two squadrons abreast with the third squadron above and slightly behind the other two. Generally speaking, the results of the escort missions were meager, and disappointing primarily because there was nothing to shoot at. The greatest number of enemy seen in the air at any one time was forty A/C on the mission of 10 June. None or almost none of the Japs seen tried to attack the B-29’s; several of them were probably spotters for AA batteries and most of them, after they wore sighted, acted as though they had arrived in the area by mistake. Properly speaking, the 506th ’s role on these affairs was not “escort” at all.

Jap air strength in late May, when the Group was set up to operate, had diminished to such a point and their policy of cautious conservation had been carried to such extreme that a vicious all out air battle between escorting planes and a swarm of attacking fighters, such as had developed in the air-war over Europe, was out of the question. Consequently, when any of the Group pilots did sight the Nips in the air, it was a mad scramble to see who could get there first and register the kill. The bomber stream was left miles behind; against a determined enemy attacking in force, this would have been a serious inconvenience for the B-29’s, but under the “bush-league” conditions, which governed aerial combat in the last stages of the war, it was the proper policy. When interception or the presence of the enemy was sighted, control was vested in the Squadron Leader to dispatch fighters in sufficient numbers to deal with the hostile aircraft. Because the tactical conditions had not required it, coordination of these squadron efforts by the Group Commander was not attempted.

Original photo of a B-29's nose art. This B-29 Superfortress belonged to the 874th Bomb Squadron, who were based in Saipan.

Effective escort was rendered doubly difficult, had it been required, by the loosely strung out formation necessarily employed by the B-29’s. Patrolling up and down the “stream” of bombers, is a different matter, as far as adequate protection is concerned, from escorting a closely stacked formation. The technical problems connected with the B-29 operation and the geographical situation of the theater made it impractical to have any type of formation other than “stream” but it did complicate the problems of the escorting fighters. Radio contact between the bomber leader and the fighter leader was never provided for till near the end of the war. To carry on an effective escort job liaison between the commanders involved is absolutely essential.

Finally, the one constant difficulty, the universal handicap to all phases of VLR operations was – weather. In the long trek from Iwo to the Empire, weather fronts forced abandonment of the mission. Over the target area, cloud layers and rain frequently made it impossible to establish satisfactory contact with the bombers.

Strafing Tactics

When it became obvious that we were not needed as a bomber escort force, some kind of a job had to be found for us. Airfield strafing, seeking out and destroying the enemy on his has home bases, was the logical answer to the problem. The tactical concepts involved in a ground strafing operation are very different from the problems which had to be solved on an escort mission. The most important question which we had to answer each time we undertook an airfield strike was that of the approach to the airfield. In answering this question, three things entered into our calculation:

1. Geography

2. Location of the A/F defenses

3. Dispersal area of the planes

Pilots of the 457th Fighter Squadron (from left to right): Front - Alan Kinvig, George Hetland Back - Ray Miller, Martin Ganschow, Ralph Gardner, Larry Grennan

First, geography had to do with the general layout of the field in relation to its surroundings, both natural and man made. Take Hamamatsu A/F as one example. Hamamatsu lies near the sea and other things being equal, an approach on this field from the water would not be made since such a maneuver would entail a route of withdrawal leading into rather than away from the territory of the enemy. In the case of a target like Itami, lying near the edge of a city, an attempt would be made to avoid heavily defended urban areas on both the route in and the route out. Second, unless other factors intervene, we prefer to sweep over the most lightly defended areas of the target. In many instances, the Japs, very conveniently for us, have concentrated their AA at one part of the field with the remaining sectors being defended either very little or not at all. At Kasumigaura, for instance, much of the AA is concentrated around a building area. The surrounding structures mask the five of these defenses against low flying Aircraft.

Third, disposal of aircraft, as is the case with most airfields, there were certain prearranged areas on the Jap fields at which their aircraft were habitually located. Whenever we knew where this area was, we arranged our pass so as to bring it under maximum fire of our aircraft. For some strange reason, the Japs very often cut their planes at one end of the airdrome and the heaviest cluster of AA at the other end. We were glad to take advantage of this habit whenever we found out about it. Our angle of approach, therefore, took all three of these factors into consideration. In the final tactical plan, provisions had to be made for the timing of the attack and the maneuverability of the strike force. Very frequently our squadrons hit the target from several different angles. The main thing in such multi-pronged attacks was to get our timing down so that the interval between the different approaches was as small as possible. If possible, we attempted to surprise the enemy. When we did accomplish this, as in our first mission to Hasumigaura for instance, we suspect that it was due not so much to our cleverness as to the fallings of the Nip air raid warning system.

The series of maneuvers we planned to take in the target area was transcribed to a map which was photographed and a copy of the photograph given to each pilot. For a number of reasons, our career as a ground strafing outfit was not too successful. The following factors accounted for the type of results which we achieved:

- Weather and cloud coverage over the target forced us to abandon our carefully laid plans in any number of cases. Sometimes we were weathered out of our primary target completely, and sometimes a brief hole opened in the soup and part of the strike force would barrel over the field at whatever angle was most convenient at the moment.

- Hiding of aircraft. Our program of ground strikes was never very successful after early July when the Nips began large scale concealment of their Air Force. Our successes against the Jap AF following this maneuver were indirect rather than direct. We forced them to hide their planes several miles distant, under trees and haystacks or in houses (we believe) and along the edged of narrow roads. It was impossible to see these targets or at least, to see them in time to make an effective pass on them. Had we cruised about the suspected area for time enough, and at an altitude sufficiently low to pick out these concealed targets, we would have been sitting ducks for their AA. Even had we weathered this hazard, the widely dispersed positions of the enemy planes would have proved an exceedingly difficult tactical problem. Storming up and down the woods in two or four plane elements in search of the elusive Nip, we would have run into a great deal of trouble in controlling our planes, in preventing them from interfering with one another’s field of fire, and in gathering them together to repel interception. When weather and low ceilings are added to the natural hazards of this operation, our reluctance to turn

ourselves into a moving artillery detachment became readily understandable.

- Gunnery. Our gunnery was adequate but not brilliant. Our pilots had a tendency to open up too soon and break away too quickly. Graphic demonstration of this - and this fault was by no means confined to the 506th th - was given in the gun camera film.

- Inadequate Target Information. The photo coverage of the airfields, upon which our knowledge of the AA positions and the dispersal positions was based, was inadequate and out of date. The best we could get in this department were antiquated throw-off from the XXI Bomber Command sorties. They were not in stereo, which made proper reading and interpretation difficult.

Not only should these pictures have been of more recent

dates, but we should, by all means, have had access to the Navy's coverage of Jap airfields. Beginning with the full dress carrier effort of the 10th of July they took a number of shots of the same targets at which our own attentions were directed. Someone with enough brass to do the job should have represented to the Admirals the supreme importance of letting the fighter have copies of those pictures.

Ground Strafing Targets

1st Lt. My Starin on the wing of P-51 #578 'Lil Mudcat' of the 458th FS. Note the .50 cal gun ports are taped over, keep clear of dirt, dust, and sand while parked on the ground. The six .50 caliber machine guns of the P-51 could do some heavy damage against ground targets.

About the end of July we threw in the sponge as far as airfield targets were concerned. We began to undertake target of opportunity or “rhubarb” missions. We did rather well at this. Actually, the damage that fighters can do to the enemy at this kind of work - which is, properly speaking, strategic rather than tactical in nature, is kind of small. Very few targets of opportunity are vulnerable to the fire of a .50 cal. machine gun. Railroad engines (though not always rail-road cars), transformers, high tension towers, and oil or gas storage tanks (providing their walls aren't too think), are good targets. The advisability of firing at buildings, warehouses, and ships is dubious unless they are of wood construction and even then the game may not be worth the candle unload conditions are such that the structure or the boats can be set afire.

Operations against targets of opportunity, although they are more interesting than the strafing missions over empty fields, from the pilots point of views, and though they did inflict some damage to the enemy, were not as successful as they might have been. There are three main reasons for this:

- Target of opportunity strikes were not undertaken soon enough. Long after the inadvisability of committing the Group to airfields had been demonstrated, higher echelons continued to send us out on these strikes. The fault here lay not so much with our immediate Fighter Headquarters - who were close to the problem and understood the implication - as with the High Command at Guam. No Specific Fighter Operations Staff had been set up at this Headquarters; our problems were not understood and could not have been understood on the basis of which such spotty official contacts as that provided by TWX's and mission reports and a few inspections. Iwo’s Mustangs were the orphan children of the Air War of the Pacific. Indeed, it was not until very late in the game, in August, as a matter of fact, that a liaison officer was sent from the Fighter Command to Guam to attempt a partial bridging of the gap.

- Target information was not complete, as was the case with the data available to us on the Jap airfields. Our information regarding targets of opportunity was hopelessly antiquated. Our best sources for these facts were the Air Objective Folders published by the Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Intelligence, Washington, D. C., in 1943 and sometimes early ‘44. No revisions to these documents were received. More up to date facts about oil storage points, power and radio stations, etc., should have been provided.

- Strikes against targets of opportunity were never as thoroughly planned as were our strafing attacks on airfields. At the briefing for these missions profitable targets in the area were indicated and described, but no one target, was assigned as the responsibility of a given squadron and an approach pattern worked out on a scientific basis. Some planning of this type was tentatively undertaken by one or two squadrons, but it was by no means as thorough as was the planning for our airfield strikes.

Recommendations For The Deployment of VLR Fighter Aircraft

click to open pdf

The experience of the 506th and of that VII Fighter Command on Iwo was not a typical situation as far as VLR missions are concerned. Many elements of our tour of duty in this theater will not be repeated in later operations and recommendations on them will be useless. Nevertheless, certain basic conditions for the proper employment of Air Power were violated in this theater. The only reason we were able to get away with this was that the Jap Air Force was so incredibly lousy by the time we got to it that we won no matter what we did. Our recommendations are as follows:

- The missions should not be changed without alterations of the means to its accomplishment. When the escort mission became unnecessary, we shifted to airfield and later to target of opportunity strafing; the P-51 is unsuitable for this work for reasons recognized by everyone. Indeed, the inadvisability of maintaining a large force of pursuit aircraft on Iwo once it had been declared bankrupt in its primary line of business is open to question.

- If operations are to be undertaken against ground targets, complete up to date information about these objectives is a vital necessity. The ridiculous feature of the plight of our Intelligence Departments on Iwo was that the data we needed was available in other Air Forces, or in Naval Headquarters. To allow our knowledge of the enemy to remain in various compartments hermetically, sealed from one another by red tape, represents original negligence by the responsible authorities.

- The problems of the lower operational echelons should be fully understood by higher headquarters. The Guam Headquarters, and to some extent, the Fighter Command, failed to understand the operational solutions required by the rapidly changing situation facing the Fighter Groups on Iwo. Establishment of the proper Fighter Operations Staff at Guam would have expedited the accomplishment of our mission.

Weather Forecasting For VLR Operations

Scientific weather forecasting technique, under the ideal operating conditions, is necessarily based upon information recorded simultaneously at a large number of properly placed surface reporting stations. Not only must the information be recorded at the same time at each station, but also the information from each station must be available to the using forecaster within a short period of time after it has been recorded. This information must be recorded many times each day, usually hourly, and the records kept for the total period of existence of the station. Finally, the monthly and yearly records of each reporting station should be available to the using forecaster.

The weather information that is to be recorded periodically at each surface reporting station includes such items as the sky condition, present and past weather, temperature, dew point, altitude setting, sea level pressure, pressure tendency, radioconda reports, wind direction and speed, upper level winds, spheric reports, and other special phenomenon. Using this data which was recorded at all the reporting stations at any one time, the using personnel are able to construct synoptic surface maps and additional upper level charts for any desired altitude or pressure level. From this information energy diagrams also may be constructed. Using the synoptic surface maps, upper level charts, energy diagrams, and other available data, the forecaster is able to determine the location and intensity of pressure systems and frontal systems at the time of recording of the used reports.

After the location and intensity of the pressure systems and frontal systems at map time have been determined, forecasting rules formulate, and other techniques are applied in order to prognosticate a position and intensity of the system at a future time. It is apparent that all of the above desired operating conditions do not exist in the Pacific Ocean Area. The numbers of surface reporting stations are too few and in many instances are inconveniently located due to the position of the available islands and the enemy. There is necessarily a delay in the dissemination of the little information available due to delays in communications and the use of codes. Finally, in most cases there are no monthly and yearly records of the reporting stations available to the using forecaster, as the stations are operating for the first time.

As soon as operations were begun against the enemy in advance of the boundary of the already meager reports, it was evident that additional weather information would have to be obtained. The solution to the problem was weather reconnaissance. Specially equipped bomber type aircraft with trained weather personnel aboard were to fly over enemy held territory for the purpose of obtaining weather information. These weather reconnaissance planes were dispatched from a weather forecasting central. This central, with the aid of the additional information, would publish weather forecasts for the entire area and also special operational forecasts. Because the weather reconnaissance planes at first could not radio reports while in flight and due to delays in the communications systems, there was a twelve to sixteen hour delay between the recording of the weather information and the receipt by a using station located 750 miles from the Weather Central. At the time of arrival of the 506th Fighter Group on Iwo Jima In April 1945, local area forecasting was being successfully effected by the weather stations located on the island. Due to lack of information at the weather station, the Guam Weather Central was relied upon for the major portion of the route forecasts in connection with operations between Iwo Jima and the Empire.

More the last part of May and the first part of June it became apparent to the using personnel on Iwo that additional information along the route immediately prior to the mission time was needed. Both daily and diurnal changes in the intensity of the frontal systems in the area could not always be anticipated with the amount of available information. A weather reconnaissance unit then began operating from Iwo checking weather conditions along the route of operations a few hours before take-off time. Encoded weather ports were radioed to Iwo while in flight along the routes, allowing information concerning changes in the intensity of frontal systems to be available to all concerned prior to time of take-off. After the institution of this system little difficulty in connection with changes in frontal intensity along the route from Iwo to the Empire was experienced and the resultant weather forecasts were more than satisfactory.

As soon as operations were begun against the enemy in advance of the boundary of the already meager reports, it was evident that additional weather information would have to be obtained. The solution to the problem was weather reconnaissance. Specially equipped bomber type aircraft with trained weather personnel aboard were to fly over enemy held territory for the purpose of obtaining weather information. These weather reconnaissance planes were dispatched from a weather forecasting central. This central, with the aid of the additional information, would publish weather forecasts for the entire area and also special operational forecasts. Because the weather reconnaissance planes at first could not radio reports while in flight and due to delays in the communications systems, there was a twelve to sixteen hour delay between the recording of the weather information and the receipt by a using station located 750 miles from the Weather Central.

At the time of arrival of the 506th Fighter Group on Iwo Jima In April 1945, local area forecasting was being successfully effected by the weather stations located on the island. Due to lack of information at the weather station, the Guam Weather Central was relied upon for the major portion of the route forecasts in connection with operations between Iwo Jima and the Empire.

More the last part of May and the first part of June it became apparent to the using personnel on Iwo that additional information along the route immediately prior to the mission time was needed. Both daily and diurnal changes in the intensity of the frontal systems in the area could not always be anticipated with the amount of available information. A weather reconnaissance unit then began operating from Iwo checking weather conditions along the route of operations a few hours before take-off time. Encoded weather ports were radioed to Iwo while in flight along the routes, allowing information concerning changes in the intensity of frontal systems to be available to all concerned prior to time of take-off. After the institution of this system little difficulty in connection with changes in frontal intensity along the route from Iwo to the Empire was experienced and the resultant weather forecasts were more than satisfactory.

Technical Problems Of VLR Operations

A ground crewman for the 458th FS stands near auxillary fuel tanks, or 'drop' tanks as they were known. The 506th FG P-51's mainly carried 110 gallon and 165 gallon (shown here) tanks on the long 7+ hour missions to the Japanese mainland.

When the Group arrived at Iwo, we found that no preparation had been made for conducting long range missions with the P-51.

Our first difficulty was finding material to manufacture sway braces and lines for 165 gallon external fuel tanks. The island was covered to find enough ply wood to manufacture sway braces, and with much searching and begging, we were able to get enough braces to provide tanks for our sub-covers. Tie rods for these braces were made from salvage material taken out of Jap pill-boxes, and fuel lines were removed from wrecked B-29’s. The Group had been operating over two months before suitable sway braces were supplied. Some difficulty was experienced in the 110 gallon installation in that, tanks would not release properly and in some cases, did not reload until the airplane was approaching for a landing or had contacted the runway. Several flaps were damaged by this. By using a local manufactured sway brace, which we had used on our training flights in Lakeland, and by carefully aligning the ply wood braces, provided in the tank kite, we were able to reduce the failures considerably. The last six missions no failures were reported.

The problem of furnishing men from the line to build mess halls, living quarters, and still keep enough men on the line to maintain airplanes was a headache for Engineering Officers. If the Squadron Executives and Adjutants had cooperated with the Engineering Officers, the work of camp construction could have progressed without undue hardships on the line.

Additional difficulties were experienced in that the 81st Air Service Group Engineering Section was not properly trained and organized and did not have the equipment to service us. For the first month they were not equipped to check props for balance or test for leakage. Even at this time there are no facilities for overhauling and testing of hydraulic units, pumps, coolant radiators, actuators, generators, and starters, and carburetors. All those accessories were handled by the A. R. U. ship stationed off shore and until the war was over their first priority was B-29's. Within the last month the 61st has received an instrument shop trailer and are checking and calibrating our instruments. However, no facilities are available as of yet for checking hydraulic units and carburetors.

A large percentage of our aircraft were received not suitable for combat operations. Over 30% were short DU installation when received here and were installed by our service group and by our own personnel. None of our first airplanes wore equipped with rockets and only five kits wore received. These were installed on our five oldest D-20 airplanes and were used for training in rocket firing. Airplanes received from Guam required considerable maintenance to place them in safe flying condition for the long over water flights we were required to make. There was no indication of any plans having been made previous to our arrival, to provide suitable equipment and supplies for our mission. Our operational losses would undoubtedly have been much higher if we had not had training in long range missions. Some of our earlier troubles were similar to what we had in the states and the method of correction was known.

Airplanes were delivered equipped with the K-14 gun sight which was a new type and pilots were not trained in the use of it. It was necessary to learn to use it in actual combat. Further difficulty was encountered when sights started to become worn, parts breaking etc, and it was found that no spare parts had been stocked in this control area.

Our operation was hampered still further by shortage of crew chief kits and the shortage of special tools necessary for the P-51 airplane. Kits, as now issued, are not satisfactory as many tools that are urgently needed are not authorized. No propeller special tools were received for the Hamilton Prop, therefore, composite wrenches were manufactured locally. Shortage of some OEL equipment has caused delay and extra work in some squadrons. One squadron found after uncrating their equipment that the hydraulic test stand was missing. While another squadron was short the A-7 engine hoist. When these items were needed, it was necessary to borrow from another squadron, and usually had to wait until the squadron was finished with it.

Rust and corrosion presented quite a problem throughout our operations. It was held to a minimum by constant cleaning and maintenance. First trouble was the rusting and sticking of poppet valves which actuated landing gear and flaps. This was corrected by thoroughly cleaning and keeping the poppets’ covered with a thick coat of grease, which would be cleaned off weekly and recoated. Until our parking ramps were surfaced, the dust caused some trouble by clogging impact tubes and filters.

Orders were issued that impact tubes, carburetors screens, and filters would be cleaned prior to each long range mission. Since moving to hard surfaced areas very little trouble of this nature has been experienced.

In the early stages of our operations, some trouble was experienced with spark plugs. Our experience while running long range missions in the states helped correct this unsatisfactory condition, by constructing cabinets which could be heated so as to keep the moisture from forming on electrodes and corroding. Only certain mechanics were authorized to set the gaps and mechanics installing plugs were repeatedly cautioned about using proper torque on installation. Resistors and leads were carefully checked at time plugs were installed. This procedure with the instructions given the pilot as to properly clearing engine and using full power on take-off eliminated entirely our previous trouble of engines cutting out on take-off.

Fuel external tanks failing to draw fuel after taking off on long range missions gave us some headaches until it was discovered that the seals which were manufactured by the A. R. U. were not satisfactory. Proper Neoprene seals eliminated this condition.

Magnetos have given us some trouble after having reached 200 hours operation. This was on a series of Magnetos which had an unsatisfactory bearing which would not retain the grease. There are still some installed but are being replaced with modified Magnetos as rapidly as possible.

Carburetors have given us considerable trouble. First trouble was caused by sand getting into carburetor and clogging air passages, boost venture, on enrichment valve, and diaphragm also scoring of vapor vent float needles. This condition was cleared up since airplanes were moved into hard surface areas, but trouble is still being experienced since starting to use overhauled carburetors; also carburetors coming with new engines, in some cases are improperly prepared for storage and rust and corrosion has started to form. The 81stService Group Engineering does not have the equipment to flow test carburetors and the A. R. U. will not flow test unless requested to do so. If a request is made to flow test a carburetor, it must go through the materiel squadron where work order is prepared, and then sent to A. R. U. Due to transportation difficulties, it usually takes a day to reach the A. R. U. where it is tested and it returns the third day. This is much time lost and the entire operation could be performed and carburetor installed back in the airplane in one half day if the service squadron was equipped with a flow bench.

Most all our difficulties have been (1) shortage of supplies, due to inexperience in not anticipating the needs for an operation of the kind we were engaged in and too much delay in getting organized; (2) Maintenance in engineering shops hold up due to inexperience and proper organization plus their own supply difficulties; (3) Time lost in waiting on supplies on third echelon maintenance; (4) Due to inexperience in our own organization in getting organized.

Our accomplishments have not been numerous but we can point with pride to our maintenance record which has been accomplished, by the crew chiefs and mechanics taking great pride in their airplanes. Those men have performed their duty in a commendable manner. Technical orders and modifications have been accomplished while performing aerial missions. Very few technical orders remain to be accomplished; parts for them are on requisition. Major modifications have been: Installation of DU, Emergency Release for coolant radiator flaps, rocket installation on five airplanes, and installation.

Recommendations for future VLR Missions

- That advantage be taken of the knowledge gained in tests and experiments at Wright Field and Orlando and close relations be maintained between those centers and the organization operating long range missions.

- That careful planning missions be made, to provide equipment suitable for this type of mission. Airplanes to be: completely equipped for combat, long range operation, radio aids, safety features, and roomy, comfortable cockpits for pilots.

- That table of organization and equipment be completely revised to meet the requirements of this special mission, providing men and equipment for consolidated maintenance on P.L.M.

- That a higher trained and organized service group be assigned each VLR Group which has all special equipment to completely service combat group. This service group should be directly under the control of the tactical commander.

- That a special table of supplies be drawn up for the organization operating VLR missions, taking into consideration the type of airplanes assigned and the location, and this stock maintained at a high level at all times.

(Note) : This table cannot be satisfactorily written by people who do not have experience in actual airplane maintenance.

The squadrons were using F-3 Refueling Units which made the task of refueling airplanes difficult, since the F-3 Unit held 750 gallons and each plane needed 489 gallons for full servicing. It required much time and effort to refuel all necessary planes for a mission.

Supply difficulties were also encountered in the procurement of supplies for the proper maintenance of the aircraft. The Air Service Group was not experienced in the needs of a P-51 Group, consequently did no maintain a proper 30-day level of critical items that were needed by the squadrons.

On a requisition to Guam Air Depot, the depot would return the requisition requesting more data and basis for requisition. This caused great delay in obtaining the critical part.

Operational Difficulties in Connection with Ordnance Functional

The major difficulty occurred when the only available .50 cal. Ammunition proved to be defective and had to be classed Grade 3. The lack of missions and the location of a surplus in an Anti-Aircraft battery, prevented us from being completely out.

Another situation in supply held up the rocket firing. Because of the small number of 5.0” HVAR and 5.0” AR reaching this island, we were unable to train and fire rockets to any great affect. The lack of Rocket Launcher Kits also restricted our number of rocket carrying aircraft to no more than six (6) at any time.

Even though there is a very rapid and peculiar wet rust in this area, we have never been able to get a sufficient amount of paint metal primer. This should be used on all metal surfaces, such as weapons and vehicles, before the outer coating of paint is applied. The present O.D. paint is very poor as protecting for metal. It has a very short wearing life and it is believed its original purpose as a camouflage paint is all that it should be used for. There is a very definite need for a metal enamel or a harder and more durable metal paint.

Difficulties Encountered by Armament on VLR Operations

A pair of P-51 Mustangs from the 458th FS (near) and 457th FS being serviced. The ground crewman closest in the picture is tending to the .50 caliber ammo storage in the wing for the P-51's 6 machine guns (3 in each wing). The Mustang could hold a total of 1,840 rounds between the six guns.

The principal difficulty encountered by the Armament Sections was the K14A Gun Sight. The sight, being a delicate gyroscopic instrument, could easily become inoperative between the base and the target, or over the target, without any prior warning. This necessitated use of the fixed portion of the sight which is equipped with a 70 mil reticle and this was particularly bad due to the fact that all our pilots had been trained to fight on a 100 mil reticle.

A very definite supply problem was also encountered with the sight in our first two months of operation. No replacement parts of new sights were available, and no facilities for the repair of this sight were at hand. A limited number of K-14 sight installation kits were available and were tried with unsuccessful results.

Another problem which fell to the Armament Sections was "wing tank trouble". This means simply that when the planes reached the point of release for the tanks, some of them almost invariably failed to drop. This put the pilot at a disadvantage in several ways such as the possibility of ground fire hitting the tank, reducing speed of the plane somewhat, as well as increasing consumption of gasoline which was all important.

This problem was finally licked by cleaning the bomb shackles prior to such VLR, using metal sway braces which could not bind on the tanks, or if wooden sway braced were used, exercising extreme care to make certain the tanks were properly adjusted and aligned.

Pilots, too, were instructed on the best methods of release to be employed where possible such as diving and then pull out sharply while firing a burst from machine guns, or slowly up and lowering the flaps and landing gear, etc.

No real difficulty was encountered with the guns and gun camera. Only one instance of unserviceable ammunition was encountered and this was disposed of as soon as it was discovered. Only one squadron was involved in this bad ammunition.

The service test of stallite lined barrels performed by 462nd Fighter Squadron showed that approximately 2000 rounds of ammunition is the maximum which can be fired without changing, when firing up to 250 rounds in each burst as is often the case on strafing missions. However, this is a great improvement over the old tyon barrels as they average approximately 1000 rounds, under the same conditions.

Recommendations

It is recommended that stallite lined barrels be used exclusively in combat.

Communications

Radio Communications: VHF Radio communications was hampered mainly by the limited number of channels using the SCR-522. Efficient use was made of the four channels but the traffic handled on each channel was too great to make communications operate perfectly. This is shown in the fact that communications during one-group strikes was very good, while during strikes involving two or more groups, chatter on the two “common-channels”, ”B” and “C”, made communications very difficult. Maximum traffic was on “B” channel (Bomber to Fighter) while over the rally point during which time fighters were trying to locate the Navigator B-29’s, the B-29’s were getting formation and deciding who would go on course etc. Traffic on “C” Channel (Air Sea Rescue) was very heavy at the rally point and it was found that during four group strikes it was next to impossible to get a message through during that one hour period in which fighters were rallying. The volume of traffic while over the target and at the rally point was too great on the fighter group frequency, “A” Channel. The amount of traffic could have been cut down considerably if radio discipline had been used to a great extent. All transmissions were not of an emergency nature and were not absolutely important to the conduct of the mission. “C” Channel was used as Tower Common at Iwo which further congested this important (Air Sea Rescue) channel on the return to Iwo.

Recommendations

A ground crewman for the 458th FS stands near auxillary fuel tanks, or 'drop' tanks as they were known. The 506th FG P-51's mainly carried 110 gallon and 165 gallon (shown here) tanks on the long 7+ hour missions to the Japanese mainland.

When the Group arrived at Iwo, we found that no preparation had been made for conducting long range missions with the P-51. Our first difficulty was finding material to manufacture sway braces and lines for 165 gallon external fuel tanks. The island was covered to find enough ply wood to manufacture sway braces, and with much searching and begging, we were able to get enough braces to provide tanks for our sub-covers. Tie rods for these braces were made from salvage material taken out of Jap pill-boxes, and fuel lines were removed from wrecked B-29’s. The Group had been operating over two months before suitable sway braces were supplied. Some difficulty was experienced in the 110 gallon installation in that, tanks would not release properly and in some cases, did not reload until the airplane was approaching for a landing or had contacted the runway. Several flaps were damaged by this. By using a local manufactured sway brace, which we had used on our training flights in Lakeland, and by carefully aligning the ply wood braces, provided in the tank kite, we were able to reduce the failures considerably. The last six missions no failures were reported.

The problem of furnishing men from the line to build mess halls, living quarters, and still keep enough men on the line to maintain airplanes was a headache for Engineering Officers. If the Squadron Executives and Adjutants had cooperated with the Engineering Officers, the work of camp construction could have progressed without undue hardships on the line. Additional difficulties were experienced in that the 81st Air Service Group Engineering Section was not properly trained and organized and did not have the equipment to service us. For the first month they were not equipped to check props for balance or test for leakage. Even at this time there are no facilities for overhauling and testing of hydraulic units, pumps, coolant radiators, actuators, generators, and starters, and carburetors. All those accessories were handled by the A. R. U. ship stationed off shore and until the war was over their first priority was B-29's. Within the last month the 61st has received an instrument shop trailer and are checking and calibrating our instruments. However, no facilities are available as of yet for checking hydraulic units and carburetors.

A large percentage of our aircraft were received not suitable for combat operations. Over 30% were short DU installation when received here and were installed by our service group and by our own personnel. None of our first airplanes wore equipped with rockets and only five kits wore received. These were installed on our five oldest D-20 airplanes and were used for training in rocket firing. Airplanes received from Guam required considerable maintenance to place them in safe flying condition for the long over water flights we were required to make. There was no indication of any plans having been made previous to our arrival, to provide suitable equipment and supplies for our mission. Our operational losses would undoubtedly have been much higher if we had not had training in long range missions. Some of our earlier troubles were similar to what we had in the states and the method of correction was known.

Airplanes were delivered equipped with the K-14 gun sight which was a new type and pilots were not trained in the use of it. It was necessary to learn to use it in actual combat. Further difficulty was encountered when sights started to become worn, parts breaking etc, and it was found that no spare parts had been stocked in this control area. Our operation was hampered still further by shortage of crew chief kits and the shortage of special tools necessary for the P-51 airplane. Kits, as now issued, are not satisfactory as many tools that are urgently needed are not authorized. No propeller special tools were received for the Hamilton Prop, therefore, composite wrenches were manufactured locally. Shortage of some OEL equipment has caused delay and extra work in some squadrons. One squadron found after uncrating their equipment that the hydraulic test stand was missing. While another squadron was short the A-7 engine hoist. When these items were needed, it was necessary to borrow from another squadron, and usually had to wait until the squadron was finished with it.

Rust and corrosion presented quite a problem throughout our operations. It was held to a minimum by constant cleaning and maintenance. First trouble was the rusting and sticking of poppet valves which actuated landing gear and flaps. This was corrected by thoroughly cleaning and keeping the poppets’ covered with a thick coat of grease, which would be cleaned off weekly and recoated. Until our parking ramps were surfaced, the dust caused some trouble by clogging impact tubes and filters. Orders were issued that impact tubes, carburetors screens, and filters would be cleaned prior to each long range mission. Since moving to hard surfaced areas very little trouble of this nature has been experienced.

In the early stages of our operations, some trouble was experienced with spark plugs. Our experience while running long range missions in the states helped correct this unsatisfactory condition, by constructing cabinets which could be heated so as to keep the moisture from forming on electrodes and corroding. Only certain mechanics were authorized to set the gaps and mechanics installing plugs were repeatedly cautioned about using proper torque on installation. Resistors and leads were carefully checked at time plugs were installed. This procedure with the instructions given the pilot as to properly clearing engine and using full power on take-off eliminated entirely our previous trouble of engines cutting out on take-off. Fuel external tanks failing to draw fuel after taking off on long range missions gave us some headaches until it was discovered that the seals which were manufactured by the A. R. U. were not satisfactory. Proper Neoprene seals eliminated this condition.

Magnetos have given us some trouble after having reached 200 hours operation. This was on a series of Magnetos which had an unsatisfactory bearing which would not retain the grease. There are still some installed but are being replaced with modified Magnetos as rapidly as possible. Carburetors have given us considerable trouble. First trouble was caused by sand getting into carburetor and clogging air passages, boost venture, on enrichment valve, and diaphragm also scoring of vapor vent float needles. This condition was cleared up since airplanes were moved into hard surface areas, but trouble is still being experienced since starting to use overhauled carburetors; also carburetors coming with new engines, in some cases are improperly prepared for storage and rust and corrosion has started to form. The 81stService Group Engineering does not have the equipment to flow test carburetors and the A. R. U. will not flow test unless requested to do so. If a request is made to flow test a carburetor, it must go through the materiel squadron where work order is prepared, and then sent to A. R. U. Due to transportation difficulties, it usually takes a day to reach the A. R. U. where it is tested and it returns the third day. This is much time lost and the entire operation could be performed and carburetor installed back in the airplane in one half day if the service squadron was equipped with a flow bench.

Most all our difficulties have been (1) shortage of supplies, due to inexperience in not anticipating the needs for an operation of the kind we were engaged in and too much delay in getting organized; (2) Maintenance in engineering shops hold up due to inexperience and proper organization plus their own supply difficulties; (3) Time lost in waiting on supplies on third echelon maintenance; (4) Due to inexperience in our own organization in getting organized. Our accomplishments have not been numerous but we can point with pride to our maintenance record which has been accomplished, by the crew chiefs and mechanics taking great pride in their airplanes. Those men have performed their duty in a commendable manner. Technical orders and modifications have been accomplished while performing aerial missions. Very few technical orders remain to be accomplished; parts for them are on requisition. Major modifications have been: Installation of DU, Emergency Release for coolant radiator flaps, rocket installation on five airplanes, and installation.

Recommendations for future VLR Missions

- That advantage be taken of the knowledge gained in tests and experiments at Wright Field and Orlando and close relations be maintained between those centers and the organization operating long range missions.

- That careful planning missions be made, to provide equipment suitable for this type of mission. Airplanes to be: completely equipped for combat, long range operation, radio aids, safety features, and roomy, comfortable cockpits for pilots.

- That table of organization and equipment be completely revised to meet the requirements of this special mission, providing men and equipment for consolidated maintenance on P.L.M.

- That a higher trained and organized service group be assigned each VLR Group which has all special equipment to completely service combat group. This service group should be directly under the control of the tactical commander.

- That a special table of supplies be drawn up for the organization operating VLR missions, taking into consideration the type of airplanes assigned and the location, and this stock maintained at a high level at all times.

(Note) : This table cannot be satisfactorily written by people who do not have experience in actual airplane maintenance.

The squadrons were using F-3 Refueling Units which made the task of refueling airplanes difficult, since the F-3 Unit held 750 gallons and each plane needed 489 gallons for full servicing. It required much time and effort to refuel all necessary planes for a mission.

Supply difficulties were also encountered in the procurement of supplies for the proper maintenance of the aircraft. The Air Service Group was not experienced in the needs of a P-51 Group, consequently did no maintain a proper 30-day level of critical items that were needed by the squadrons. On a requisition to Guam Air Depot, the depot would return the requisition requesting more data and basis for requisition. This caused great delay in obtaining the critical part.

Operational Difficulties in Connection with Ordnance Functional

The major difficulty occurred when the only available .50 cal. Ammunition proved to be defective and had to be classed Grade 3. The lack of missions and the location of a surplus in an Anti-Aircraft battery, prevented us from being completely out.

Another situation in supply held up the rocket firing. Because of the small number of 5.0” HVAR and 5.0” AR reaching this island, we were unable to train and fire rockets to any great affect. The lack of Rocket Launcher Kits also restricted our number of rocket carrying aircraft to no more than six (6) at any time.

Even though there is a very rapid and peculiar wet rust in this area, we have never been able to get a sufficient amount of paint metal primer. This should be used on all metal surfaces, such as weapons and vehicles, before the outer coating of paint is applied. The present O.D. paint is very poor as protecting for metal. It has a very short wearing life and it is believed its original purpose as a camouflage paint is all that it should be used for. There is a very definite need for a metal enamel or a harder and more durable metal paint.

Difficulties Encountered by Armament on VLR Operations

A pair of P-51 Mustangs from the 458th FS (near) and 457th FS being serviced. The ground crewman closest in the picture is tending to the .50 caliber ammo storage in the wing for the P-51's 6 machine guns (3 in each wing). The Mustang could hold a total of 1,840 rounds between the six guns.

The principal difficulty encountered by the Armament Sections was the K14A Gun Sight. The sight, being a delicate gyroscopic instrument, could easily become inoperative between the base and the target, or over the target, without any prior warning. This necessitated use of the fixed portion of the sight which is equipped with a 70 mil reticle and this was particularly bad due to the fact that all our pilots had been trained to fight on a 100 mil reticle. A very definite supply problem was also encountered with the sight in our first two months of operation. No replacement parts of new sights were available, and no facilities for the repair of this sight were at hand. A limited number of K-14 sight installation kits were available and were tried with unsuccessful results. Another problem which fell to the Armament Sections was "wing tank trouble". This means simply that when the planes reached the point of release for the tanks, some of them almost invariably failed to drop. This put the pilot at a disadvantage in several ways such as the possibility of ground fire hitting the tank, reducing speed of the plane somewhat, as well as increasing consumption of gasoline which was all important. This problem was finally licked by cleaning the bomb shackles prior to such VLR, using metal sway braces which could not bind on the tanks, or if wooden sway braced were used, exercising extreme care to make certain the tanks were properly adjusted and aligned.

Pilots, too, were instructed on the best methods of release to be employed where possible such as diving and then pull out sharply while firing a burst from machine guns, or slowly up and lowering the flaps and landing gear, etc.

No real difficulty was encountered with the guns and gun camera. Only one instance of unserviceable ammunition was encountered and this was disposed of as soon as it was discovered. Only one squadron was involved in this bad ammunition.

The service test of stallite lined barrels performed by 462nd Fighter Squadron showed that approximately 2000 rounds of ammunition is the maximum which can be fired without changing, when firing up to 250 rounds in each burst as is often the case on strafing missions. However, this is a great improvement over the old tyon barrels as they average approximately 1000 rounds, under the same conditions.

Recommendations

It is recommended that stallite lined barrels be used exclusively in combat.Communications

Radio Communications: VHF Radio communications was hampered mainly by the limited number of channels using the SCR-522. Efficient use was made of the four channels but the traffic handled on each channel was too great to make communications operate perfectly. This is shown in the fact that communications during one-group strikes was very good, while during strikes involving two or more groups, chatter on the two “common-channels”, ”B” and “C”, made communications very difficult. Maximum traffic was on “B” channel (Bomber to Fighter) while over the rally point during which time fighters were trying to locate the Navigator B-29’s, the B-29’s were getting formation and deciding who would go on course etc. Traffic on “C” Channel (Air Sea Rescue) was very heavy at the rally point and it was found that during four group strikes it was next to impossible to get a message through during that one hour period in which fighters were rallying. The volume of traffic while over the target and at the rally point was too great on the fighter group frequency, “A” Channel. The amount of traffic could have been cut down considerably if radio discipline had been used to a great extent. All transmissions were not of an emergency nature and were not absolutely important to the conduct of the mission. “C” Channel was used as Tower Common at Iwo which further congested this important (Air Sea Rescue) channel on the return to Iwo.Recommendations: More efficient operation of the Uncle Dog could have been effected at the rally point if a transmitter of higher wattage output had been used instead of the SCR-522. A more powerful transmitter would have overcome the effect of the Jap radar at the rally point and would enable the pilots to receive D/U on the target.

A visual, left, on course, and right indicator would be more satisfactory than the aural signal now used. It is believed this modification on the AN/ARA-6 is now being made and other information from the S-2, a decision is made as to the course to be pursued and the tactics to be followed. Leadership of VLR missions is rotated among the wheels of the Group: Col. Harper. CO; Lt. Col. Brown, Deputy CO; Maj "Muddy” Watters. Operations, Capt. Anthony. CC of the 457th; Maj. Shipman, CO of the 458th; 13aj DeJarnette, CO of the 462nd. In the Squadrons the CO, the operations officer, or selected flight leaders may serve as the unit leader. The plane to pilot ratio is such that the pilot is ordinarily scheduled to fly almost every mission.

Training for Combat

The training and refresher program during June was on a comparatively modest basis. For the training and combat indoctrination of replacements pilots reliance was placed on CAP sorties and Bonins "training" missions. In general it was determined that instruction of the replacements should be done by the Squadrons rather than by the Group* Formal classroom instruction was held to minimum in all save two departments, air sea rescue and recognition. About 8 hours of lectures and demonstration were devoted to ASR procedure, survival, use of survival equipment and related subjects, proficiency in the recognition of aircraft and surface vessels, friendly and enemy, was maintained by a classroom schedule of about 2 hours per week. Our knowledge of the ED and the K14A, gunsight, gadgets that we had no opportunity to become familiar with during Stateside training, was augmented by edge of the target to allow for foreshortening. The diamonds were obscured, it was noted, and difficulty was encountered in bracketing due to the white backgrounds of the sleeve target against the clouds.

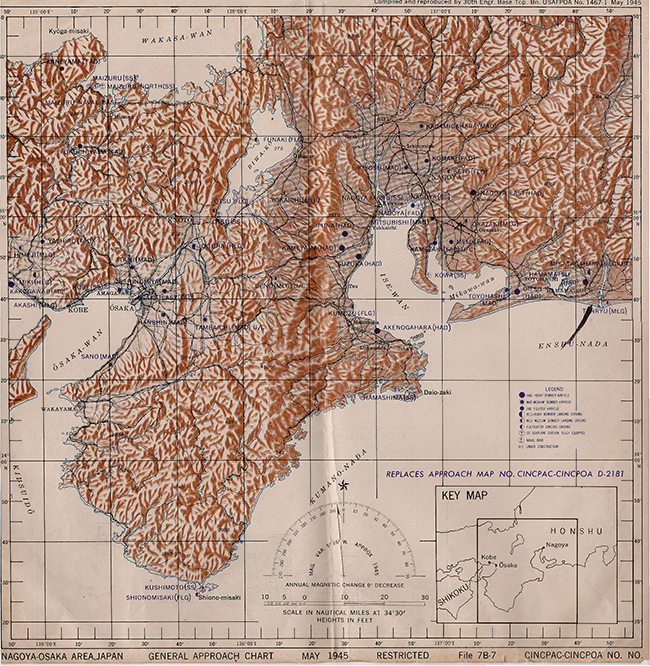

Map of Nagoya-Osaka area of Japan from May 1945. Maps like this were used in mission planning.

Service Operations

Engineering, Ordnance, Armament, and Supply

Gradually the Squadron maintenance sections are beginning to acquire the “know how” needed for efficient operation under the conditions prevailing on Iwo. Learning how to combat dust and corrosion, how to get along without necessary tools and equipment, how to stretch their meager stock of spare parts — these were the fruits of their experience. Dust, of course, was a problem for which special protective measures had to be taken constantly. In the 457th, for example, a sheet metal cover was devised and later adopted by the ether two Squadrons, which 5lamped over the case ejection chute openings for the .50 caliber guns while the plane was on the ground and prevented dirt and grit from being swept into the guns Many of the more interesting problems which arose during the month centered around the K14A gunsight. Replacements, spare parts, and kits for the sight are not to be had, in fact several a while that the Kl4 kits on hand could be used for the K14A, but this hope proved abortive because the parts required for the K14A were not interchangeable with the equipment found In the kits designed for its predecessor. The original intention of installing new sights after each 100 hours of operation was abandoned in favor of the present procedure, as prescribed in a tech order lately received, of thoroughly cleaning, inspecting and oiling the sight ever 25 operational hours. The sight just be turned on during taxiing and take off to prevent the jeweled bearings in the gyro from being dislodged by the vibration. Before corrective action was taken, the pilot, with the sight on would sometimes absentmindedly flick the gun camera trigger switch on the control stick starting the cameras and, of course, wasting film. The trick, there was to rig up a wiring system in which the sight would operate even though the gun camera safety switch was turned off. The solution to the problem was originally suggested by Lt Hines of the 458th in Tinian and was gradual adopted by the rest of the Group. The remedy consisted in removing the extreme right lead from the "Guns Camera and Sight" position and hooking it onto the “Camera and Sight" post aborting out the gunsight wire through the gun camera safety switch with the result that the sight is cow control by the "off-on” switch in the K14A, selector and dimmer rocket launchers for our aircraft remained the only outstanding shortage in the Group's combat equipment.

By 15 June, 5 planes had been fitted out for carrying the 5” HVAR or the 5” AH projectile. The installation in 3 of the planes included the wiring, the racks, and the intervalometer; two of the aircraft being of a somewhat newer type were already equipped with internal wiring and required only the racks and the intervalometer. Regardless of the fact that a Squadron or two of rockets would hare materially contributed to the success of our Empire missions it proved impossible to obtain kits end equipment for additional rocket ships. Far more than the average amount of propeller and carburetor trouble was encountered during the tenth. Prop trouble in the form of oil leaks at both the cone and the spider shaft was due primarily to the ersatz fiber type seal palmed off on us by the supply agencies as a replacement for the old reliable Neoprene seal. Oil leaks involve, ordinarily, no more than a droplet or two of fluid which escapes from the prop connection and splatters over the windshield at high velocity obscuring the pilots’ forward vision. During June, as many as 5 aircraft at a time were grounded because of oil leaks. The Neoprene seals to remedy this state of affairs were dribbling in a few at a time through normal supply channels and a few were being chiseled.