2nd Lt. William Glen Ebersole | Jim Bercaw

also go to the modelers page

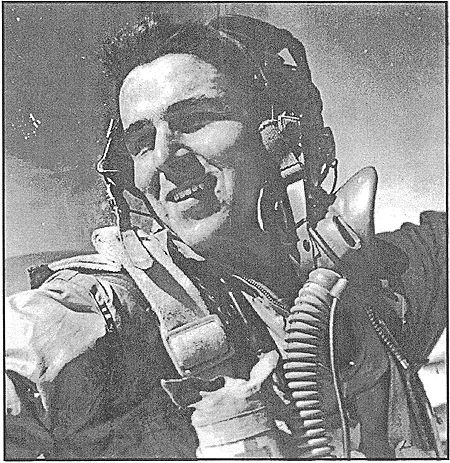

Pilots: Bill Ebersole/Jim Bercaw | Rank: 2 Lt | Squadron: 462nd | Plane: #619 Hon Mistake | S/N: 472587

THE AIR CORPS YEARS

(1942-1946)

William Glenn Ebersole was born in Arcadia, Florida, on September 30, 1924. He graduated from DeSoto County High School on June 6th, 1942 and entered the University of Florida in Gainesville as a freshman in September, 1942.

Concerned about the possibility of being drafted into service in World War II; with the U.S. got direct involvement about 9 months old, with four others from the same dormitory section, I went to the U. S. Army Air Corps recruiting office in downtown Gainesville to inquire about the benefits of joining the Air Corps. We took the written and physical exams. I was certain in my own mind that I would never be able to pass the eye exams because of an accident when I was 10 or 11 years old. I was in my back yard in Arcadia with by Daisy pump-action BB gun at my side; I was waiting for a noisy woodpecker to come around to the other side of a make-shift flag pole we had on a piano-box clubhouse in our back yard. Brother Bob slipped his hand through the fence and pulled the trigger to surprise me and I was shot in the eye at close range. The glancing shot made a perfect round hole in my eyelid, but never penetrated my eyeball. I was always certain it affected my vision. The Air Corps said it didn't.

The other three, for various reasons, did not make the cut. Lucky me; as of October 31, 1942, almost a month to the day from my 18th birthday, I was in the Air Corps Reserve and felt assured that I would get at least two years of college completed before I had to go on active duty. I was hoping that maybe it would be over by then. Even if it wasn't, the Air Corps was a nice safe branch of the service because we would most likely be away from any real enemy action. It sounded a whole lot better than the infantry.

I thought it might be interesting to learn to fly but I was never as caught up with the idea of flying like my younger brother Dan. He could quote you the names and performance records of almost anything that flew.

I had always been an outdoors type of person, and never much on reading. Even though I only weighed about 125 pounds when I graduated from high school, I was a heavy participant in all types of sports. I had high school letters in football, baseball, and swimming and played on a local softball team. I was fair at a lot of things but not excellent in any. With friends I spent a great deal of time camping, hunting and fishing and I was an Eagle Scout. In college I wanted to learn a profession that would keep me outdoors and because I was reasonably good at math and science in high school I decided to study civil engineering. I was only one week into my second semester in early February 1943, when the word started circulating around the UF campus that the Air Corps Reserve had been activated. I checked my local mail, but there was nothing. I called my father in Arcadia. He said that yes, I had a letter there. He opened it and read it to me. I was to report for active duty on February 24, 1943 in Miami Beach, Florida. I resigned from the University, packed my things, and took a bus back to Arcadia. I had about a week before I had to be in Miami Beach. Most of the new recruits that were together in Miami Beach were from the University of Florida so I had a number of friends and acquaintances there for our one month indoctrination and basic training program.

We stayed at the Blackstone Hotel and almost every day marched down Collins Avenue to the golf course for close-order drills, and singing Air Corps songs at the top of our lungs. At the end of a month, we were shipped by train for a month-long stay at a classification center in Nashville, Tennessee. There, we underwent a number of written and physical tests to determine the area of specialization for which we were best suited.

Most were classified as bombardier, navigator or pilot. I was trying for pilot knowing that the other options were available in case that didn't work out for me. I was elated when I found out that pilot was the training for which I was selected. To even out the flow of pilots into the flight schools, some of us were side-tracked into units that were designated College Training Detachments. I was assigned a 4-month stay at Clemson College in South Carolina where we were to receive some basic college training for three months and some elementary flight instruction in cub training planes the final month. I was advanced one month in the program so missed the flight instruction.

From Clemson I was shipped to Maxwell field for a 60-day preflight program. When the assignments came out for primary flight school, I was surprised to find out that even though the group which I had been with since Miami Beach was being sent to training schools in Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas, I was alone in being sent to the primary flight training school in Arcadia, Florida, where I was born and raised. As I later discovered, my father's partner in the Arcadia newspaper, Nate Reece, had some contacts through the local flight school and had requested that I be sent there. So I left the friends I had made thus far and began anew my flight career in my hometown.

From Clemson I was shipped to Maxwell field for a 60-day preflight program. When the assignments came out for primary flight school, I was surprised to find out that even though the group which I had been with since Miami Beach was being sent to training schools in Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas, I was alone in being sent to the primary flight training school in Arcadia, Florida, where I was born and raised. As I later discovered, my father's partner in the Arcadia newspaper, Nate Reece, had some contacts through the local flight school and had requested that I be sent there. So I left the friends I had made thus far and began anew my flight career in my hometown.

Primary flight school in the 220 horsepower Stearman PT-17 bi-wing trainer was especially easy for me for several reasons. I couldn't have possibly gotten lost because I was flying over the same country here I had been hunting and fishing for as long as I could remember. I was told that the cub flying that most of the cadets had but which I missed when I was advanced one class turned out to be more of a hindrance than a help because many of the things had to be un- learned that were taught there. My first ride in the PT-17 was on October 5, 1943 and my first solo flight was two weeks and 8 1/2 hours of dual instruction time later on October 19, 1943.

In primary training, each cadet was scheduled for about sixty hours of actual flying time, divided into 20 hours of basic flying, 20 hours of more advanced chandelles, lazy eights, pins, etc., and a final 20 hours of advanced maneuvers and acrobatics. A routine check ride was given after completing each 20 hour phase. After only a little more than 30 hours total time, my instructor resigned and each of the four of us in his flight group were given check rides to see how we had progressed. After my check ride, I was told that I had successfully completed my 40-hour check and was free to begin the advanced phase of acrobatics including slow rolls, snap rolls, loops, emmelman turns, and other advanced acrobatics, which other pilots couldn't begin until their 40-hour check rides were completed. In some cases this didn't occur until after 50 or more hours.

Because of my early start in acrobatics I became quite proficient and was selected from my squadron of about thirty pilots to perform in the acrobatic demonstration and competition during our graduation exercise at the end of our primary training on December 4th, 1943. My parents were invited out to witness the program. Of course in all of the excitement the slow roll I did wasn't up to what I was capable of doing and was a bit sloppy so I lost out to the other squadrons. Nevertheless, I was glad I had a chance to show off a little for my folks.

My next stop was two months of basic training at Gunter Field, Montgomery, Alabama, where we flew the 450 horsepower BT-13. It was a large low-wing plane with a two-speed propeller and fixed landing gear. Acrobatics that we had learned in primary training were not allowed so this part of our training was shelved until later. Here we were introduced to Link trainers and instrument flying, night flying, blackout landings, formation flying and other things.

I arrived at Craig Field, Selma, Alabama for advanced flight training in mid-February, 1944, and there completed another 68 1/2 hours of flying time in the North American AT-6 advanced trainer. The AT-6 was really a nice plane to fly. It had a controllable pitch propeller, retracdiv landing gear, and was able to handle fixed guns in the wings as well as bomb racks under them. As I recall now, it had a cruising speed of around 200 miles per hour compared to the basic trainer at 140 to 150 and the primary trainer at about 90. I completed my program there and graduated in the class of 44-D with my wings and 2nd Lieutenant Commission on April 15, 1944. We were given a short leave and then returned to Craig Field where were assigned to temporary duty at the fixed aerial gunnery training field at Eglin Field No.6, located in Florida near Panama City.

We practiced both aerial and ground gunnery flying AT-6's, and spend a large part of our spare time shooting skeet. Its purpose was to help us better understand the philosophy of leading the object we were shooting at based on the distance, speed of the object, and angle from which we were shooting. We returned to Selma where I logged my first solo flight in a full size single seat fighter plane, a P-40N, in which I flew eleven hours during the final ten days of May, 1944.

We were transferred in early June for a six-week stay in a replacement facility in Tallahassee where we waited for an opening at a fighter training base. We had ground school training but no flying time. I was elated when I learned that I would be going to the P-51 fighter training school at the Bartow Army Air Base in Florida, located between Bartow and Winter Haven. I was only 15 minutes short of having a total of 250 hours of flying time when I arrived in Bartow. I made my first flight in a P-51, model A on July 26, 1944.

We had thought we would be in Bartow for only about two months and about sixty hours of flying time when we arrived, but we weren't needed anywhere so we continued our training much longer than expected. We continued every aspect of our training, with emphasis on formation, gunnery, instrument flying, and navigation. My flying time was pretty equally divided between P-51 models A, B & C, with about a dozen hours in the first bubble-canopy plane, Model D.

Our fixed gunnery range was at Indian Rocks Beach on the Gulf Coast just south of Clearwater. They would set up a half-dozen large bulls-eye targets and we would fly a rectangular pattern at 1000 feet, diving in on the target and firing two 50-calibermachine guns, one in each wing. The aerial gunnery range was four or five miles out in the Gulf off of Clearwater stretching twenty miles or so to the north. The gunnery target was called a sleeve but it actually was a panel of wire mesh which I would estimate to be about eight feet wide by about 40 feet long with a steel bar on the leading edge weighted at the bottom by a heavy lead weight to stabilize it. It was towed by a P-51 on a steel cable about 1,000 feet long.

Toward the end of our training in Bartow, so that I could continue to log flying time, I volunteered to fly one of the tow planes and had fifteen or twenty hours of towing time before I left. To take off pulling the target was quite a trick. I would taxi out and stop at the end of the runway and flight line personnel would bring out the target and stretch it out in front and just off to the side of the runway. After the normal engine checks, I would hold the foot brakes, rev up the engine as fast as I could without nosing it over, release the breaks and give it full throttle. As soon as I had flying speed, I would lift off and climb as rapidly as I could without stalling, to minimize the distance I would be dragging the target on the runway. After flying the gunnery range route, I would return to the base, buzz the field and pull the target release lever.

The tips of the 50-caliber bullets were dipped into a powdery type paint which would leave a trace of color where it penetrated the wire mesh target. Each plane used a different color so the scores could be recorded and logged for each pilot. Because some of the target unraveled and was lost, it was measured and credit was allowed for the missing portion based on the target hits on the portion which was left.

My Bartow roommate, Alan Fort Colley, (from Decatur, Georgia) and I spent untold hours planning how to hit the ground and aerial targets and it really paid off for us. Out of the several hundred pilots in training at Bartow, he had the highest gunnery score and I was only a fraction lower with the second highest.

In ground gunnery, after we turned from the base leg onto the final approach to the target, we would carefully center the "ball" on our needle/ball indicator to assure perfect coordination, lower 10 degrees of flaps, and almost glide down onto the target, coming into closer range of the target than most of the other pilots before firing. In aerial gunnery, we would start well forward of and several thousand feet above and to the right of the target, and in a carefully coordinated maneuver, would make a rolling diving turn to the left, roll back to the right, fire at close range at a forty five degree or larger angle and fly under the target upside down if necessary to miss it. We were averaging more than 80% target hits when many of the pilots couldn't hit it at all.

When I took my last flight at Bartow on January 3, 1945, my total flying time in all of my training to date totaled 523 hours. I had flown more hours at Bartow than in all of the rest of my training combined. Most of the pilots leaving Bartow for overseas duty we found out later were being sent to the China/Burma/India theater. But a half-dozen of us were selected to fill some vacancies in a fighter group training in Lakeland. My roommate and I were both chosen for this select group and I am sure our success on the gunnery range had a lot to do with it.

We joined the 462nd Fighter Squadron in early January, 1945. It was one of three squadrons in the 506th Fighter Group in training at Drane Field in Lakeland, Florida, only a few miles from where we had been flying at the Bartow base. My first flight in Lakeland was in a P-51C on January 9th, and my final flight before going overseas was a flight on February 20th in a BT-13 to Carlstrom Field in Arcadia. One flight on January 21st was a 2,000 mile non-stop eight-hour flight using external wing tanks, which began to give us an idea of what might be in store for us when we reached a combat zone.

Each squadron in our group had double the number of pilots normally assigned to a squadron because we were told that we would be flying very long range missions and with double-strength pilots, could fly every other day if necessary. It would have been too strenuous to fly every day. Half of the pilots flew to San Francisco and left on an aircraft carrier with all of the brand new model P-51D planes we were to fly in combat. I was in the second half which took a train to Seattle and boarded a converted Swedish hospital ship. We sailed to Hawaii where we spent about two weeks, then went to Enewetok Island, then to Tinian and on to Iwo Jima.

When we arrived at Iwo, we stayed on the ship for about a week and could see the trip-flares going off all night long from some of the remaining Japanese on the island that were coming out from hiding at night. We finally landed and made our camp on the east side of the island. We slept in 4-man tents and everyone was on edge. Just before we left our ship, another group of pilots landed and almost a dozen were killed in a raid through their camp. They ran through their camp, slashed open their tents with machetes, and tossed in hand grenades. I wouldn't even sleep on my army cot for the first few weeks I was there but instead made up my bed to look like I was in it and slept on the

ground behind it with my 45 pistol by my hand, cocked and ready to fire. It is no wonder someone wasn't hurt. No one would dare leave the tent after dark because everyone was up so tight.

When we arrived at Iwo, we stayed on the ship for about a week and could see the trip-flares going off all night long from some of the remaining Japanese on the island that were coming out from hiding at night. We finally landed and made our camp on the east side of the island. We slept in 4-man tents and everyone was on edge. Just before we left our ship, another group of pilots landed and almost a dozen were killed in a raid through their camp. They ran through their camp, slashed open their tents with machetes, and tossed in hand grenades. I wouldn't even sleep on my army cot for the first few weeks I was there but instead made up my bed to look like I was in it and slept on the

ground behind it with my 45 pistol by my hand, cocked and ready to fire. It is no wonder someone wasn't hurt. No one would dare leave the tent after dark because everyone was up so tight.

We were on the island for a couple of months and watched the Seabees build our airstrip. The other group of pilots unloaded the planes at Tinian and began flying them there, waiting for the completion of the Iwo landing field. There were three different strips under construction. Ours and one other was a 5,000 foot runway, and there was a 10,000 foot one in the center of the island for emergency landings for the B-29's.

My first flight on Iwo was a local flight on May 13, 1945. I flew my first combat mission five days later when I dropped two 500-pound bombs on a radio

installation on Chichi Jima, only about a half-hour away. I was flying almost every day now on local air patrol when I was not preparing for a mission.

My first long range mission to Japan was a seven hour forty-five minute escort mission accompanying B-29's on a bombing run to Osaka, on June 7th, 1945. I made another dive bombing raid on Chichi Jima on June 11th, aborted a mission to Osaka on June 15th after 5 hours of flying time, and to Meiji on June 19th, after flying 2 1/2 hours, because of bad weather.

On June 23rd in an 8 hour mission to strafe an airfield at Hyakarigahara, I received credit for probably destroying one Zeke plane on the ground. I next flew a 7 hour mission to Suzuka on July 1st, and a second 8 hour strafing mission to Yakurigahara on July 5th. Then on July 9th, I flew an 8-hour strafing mission to Hamamatsu.

On a July 16th 7 1/2 hour mission to Akenegahara and Suzuka airfields we encountered numerous airborne planes in the Suzuka area. On a July 22nd 7 1/4 hour strafing mission to Tokeshima, Takamatou, and Micato airfields, we flew over the Inland Sea of Japan and I was the fourth plane in a 4-plane flight when our flight leader decided that we should attack an aircraft carrier. We made a near vertical dive on the carrier at full throttle from about 15,000 feet with nothing more potent than our six 50-caliber machine guns. Because I was the last of four, I was not only going the fastest but had to wait the longest before I could fire and begin pulling out of the dive. It was the fastest I ever traveled during my flying days, clocked at something over 600 miles per hour. When I pulled up I blacked out and had no idea where I was or in what direction I was heading. It was a foolish thing to do and we were lucky we weren't hit by the mass of anti-aircraft fire coming up at us.

On August 2nd, we were scheduled to hit airfields at Himeji and Itami but weather had closed these out so the squadron broke up into flights looking for accepdiv targets. We attacked some trains in a train station but there were so many planes there that we left looking for better targets. I was flying the wing of Joe Diaz over the Inland Sea when the two of us spotted a small freighter of about 100 feet in length we called a "Sugar Dog". We had plenty of time and there were only two of us there, so we set up the same type of flight pattern we used in gunnery training. When the gun camera films were reviewed, I received credit for probably destroying the ship.

My final mission was flown on August 5, 1945, the day before the atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. It was a 7 hour 15 minute strafing mission to Tachikawa. We continued to fly regular air patrol missions and some long range missions but because I had more than most, the other pilots were chosen.

A few days before my September 30th birthday, a close friend, Jim Bercaw and I told our associates to cover for us and we hitched a ride on a transport plane to Atsugi airfield in Tokyo. We spent several days bumming around and took a great many pictures which I still have. I was in Tokyo returning to Iwo on my 21st birthday.

On October 1st I volunteered, along with AI Colley, to ferry some planes to Iwo from Guam but when we got there the weather turned bad so we were stuck there until October l0th, spending most of our time looking out the canvas flap of our tent looking at the rain.

On November 16th I flew the plane that I had used on all of my missions to Guam. The engine began running rough and I was on my final approach to

Orote Field when it lost all power. I had already lowered the wheels and flaps but I had to be towed off of the runway. The planes were going to be scrapped there so the last thing I did before I got out of the plane was to remove the 8-day

spring-wound clock on the dashboard. I still have it.

I took my last flight on a P-51 on December 4, 1945, when I led a flight of 4 planes from Guam to Isley Field on Saipan. There we boarded a ship and headed back to the states. I spent Christmas and New Year's Day enroute home. When we landed at Riverside, Calif., several of us went to town as soon as we could get away and bought and drank a quart of fresh milk, something we hadn't had in almost a year.

I rode the train to Camp Blanding, Florida, received my discharge papers, spent a few days in Arcadia, and enrolled for classes beginning in February at the University of Florida.

MEDALS

Distinguished Flying Cross

Air Medal with Three Oak Leaf Clusters

Distinguished Unit Citation

Asiatic Pacific Campaign

American Campaign

Arrival time: 2/1/2026 at: 7:47:27 AM

Home | Reunions | Contact Us | VLR Story | Mustangs of Iwo Jima | Combat Camera Footage | Battle of Iwo | 457th | Webmaster ©506thFighterGroup.org. All Rights Reserved. |