Mission: Three Group VLR Fighter Strike against airfields and military installations in the Tokyo area.

Results: Three enemy aircraft probably destroyed and fourteen aircraft damaged.

Our losses: Seven P-51's and three pilots (read Warfields story). Three aircraft losses were due to flak, two to operational failure and two to unknown causes.

(1) Groups were ordered to sweep the Tokyo area. The groups again were scheduled to take off at intervals of one hour and each was assigned a search area. In these search areas three specific airfields were designated as important targets, but also to be considered as targets were all other airfields within these areas. This method proved successful. Approximately one-half of the planes sighted and damaged on this mission were on fields of minor importance, Koga, Shiroi, Kashima SS and a small airstrip near Ishioka Town. Seventeen aircraft were destroyed or damaged on the ground, and shipping, locomotives, power stations and factories were attacked during both rocket and strafing runs.

(2) In contrast to the melancholy events of the mission on 24 July, the mission turned out to be the best rhubarb of the war for the 506th. The affair was designed and executed primarily as a target of opportunity mission. Priority targets were planes in the air and on the ground, however we had just about thrown in the towel on the job of searching out and shooting up the well dispersed and cleverly camouflages remnants of the Jap Air Force. Ground targets, especially transport facilities and power lines were about all we had left to take care of. At any rate we could console ourselves with the though that "the low level of attacks by this command are believed responsible to a considerable degree for the dispersal now in effect. Our action in forcing the enemy to take such extended and over-complicated means of dispersal may in the long run lead to the deterioration of the air force. One of the enemy's weakest points has been maintenance of planes. Wide dispersal will greatly increase this problem. Moreover, his pilots will be cut short on much needed training and flying time.

IWO JIMA's P-51s AND THE LAND OF THE RISING SUN

A MISSION REPORT

BY: Jack K. Westbrook, Colonel, USAF (Ret.) 458th Fighter Squadron - 506th Fighter Group

The pilots of C Flight. Top row (l. to r.): My Starin, Robert Anderstrom, F. H. Wheeler, Jack Westbrook, William Peterson, Paul Ewalt. Bottom: Edward Kuhn, William Lockney, Goldie Marcott (Flight Commander), Donald Harris (Asst. F/CO), Francis Pilecki. (From Ralph Coltman)

|

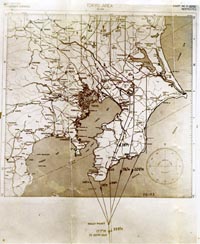

Route Navigation Map |

Bright sun and almost clear skies over Iwo Jima--a somewhat less than common state — greeted the pilots of the 506th Fighter Group 7th Fighter Command, 20th Air Force on the morning of July 28, 1945. They were as a pretty woman's come on for the weather we were to encounter during that day's fighter sweep over the Tokyo area on Japan's home island of Honshu (MAP) .

To appreciate fighter operations from Iwo Jima (MAP) and especially on this July 28 mission, one needs to know a bit about the geography and the fickle weather of this part of the world, which made fighter operations extremely perilous. Further, it is helpful to have an insight into the operational methods of the three P-51 groups-- 15th, 21st and 506th on Iwo and the one P-47 group (which arrived on Iwo in July of 1945) for these long-range flights against the Japanese homeland in World War II.

Iwo Jima is 7.5 square miles of volcanic ash and rock, situated in the vast western Pacific Ocean, some 650 miles south of Tokyo. The Bonin Islands (MAP) (Chichi Jima, Haha Jima, Ane Jima and some other smaller islands), which lie some 125 - 150 miles north of Iwo Jima, are the only significant land area between Iwo and the Japanese mainland.

Finding Japan was no problem for the P-51 pilots as we flew north from Iwo Jima; but finding Iwo--a mere speck in the great Pacific Ocean—upon return after a strike on Japan was an altogether different proposition, We had no navigators on board! The answer to the dilemma was simple: B-29 crews from the Marianas (MAP) were assigned to the fighter group, for the primary purpose of bringing the fighters home on the return flight. A B-29 was designated for each squadron and a Mustang pilot was placed aboard each B-29 as an observer to coordinate with the B-29 crew on navigation, speed, altitude and other aerial requirements of the P-51s. Even when we P-51 pilots were flying escort for the B-29s on bombing missions to Tokyo (MAP), Osaka (MAP), etc., a B-29 without payload was assigned to each P-51 squadron for navigation purposes. Some said we resembled a hen and her brood of chickens flying through the skies, an analogy a small-town 2d Lieutenant from Perry County, Tennessee, could appreciate! Usually the bomber crews were flying their last few missions before being rotated home.

Then, because of the length of these long-range missions--about seven-and-a-half hours on average—the Mustangs were rigged with two external wing tanks of some 110 gallons each. We used the fuel in these tanks as we flew north to Japan, jettisoning them at the departure point (DP) as we headed inland to make our strikes.

Another vital part of these operations was the arrangement for the rescue of the pilots who had the misfortune of having to ditch in the Pacific. Should we suffer combat damage or aircraft malfunction, we were instructed to make every effort to get out to sea before bailing out. U. S. Navy submarines, the first of four pre-positioned air-sea rescue vessels, were just a few miles off the coast of Japan, ready to pick up downed pilots. Indeed, instances of a submarine entering Tokyo Bay to rescue a downed American pilot were reported.

Destroyers, positioned about 100 miles south of the submarine patrols, comprised the next picket line of rescue vessels. Then, another 100 - 125 miles farther south the Navy had amphibious PBY Catalinas (Dumbos) ready to snatch a downed pilot out of the water. Finally, yet another 100 or so miles farther south, the Air Force placed in orbit B-17s, their bellies carrying life boats which could be dropped to a pilot in the water. These various angels of mercy saved 50 pilots during the four months of long-range missions from Iwo Jima to Japan. Sadly, 90 pilots were lost.

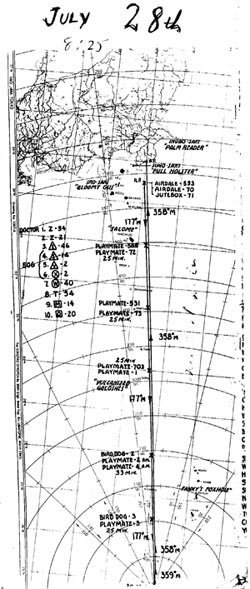

The Mustang pilots of the 506th were out of bed early on the morning of the July 28th for breakfast, mission briefing and pre-flight. The mission report of the 458th Squadron (which along with the 457th and 462nd made up the 506th Group) records that we took off at 0829 hours and arrived at our DP at 1130, some 25 miles from the coast of Japan where the Super-Forts waited in a holding pattern while the Mustangs flew on into Japan to strike airfields, industrial and other targets and then returned to form up with the Super-Forts for the return flight to Iwo.

The mission report includes this description: "For the first time, the 7th Fighter Command gave us a green light [for] a fighter sweep. The mission was pure, unadulterated rhubarb from beginning to end." The mission summary of havoc created by the 458th alone was as follows: two locomotives destroyed and two others damaged; one truck destroyed and three others damaged; two oil cars burned; one Tony (Japanese fighter) probably destroyed; two seaplanes damaged; one lighthouse damaged; one radar station set afire; three tugs set afire; one boat under construction set afire; 13 - 16 small craft set afire; and factories, power lines, railroad yards and radio stations damaged. The report included the following notation: "Lt. Westbrook hugged the deck rather firmly and shot up several factories, power lines, a railroad trestle and a steel tower near the coast. In return the enemy nicked his left wing.

The summary recorded the following losses for the 458tth; one P-51 flown by Lt. Edwin Warfield (pilot rescued); two P-51's damaged--one hit in the canopy and right wing (Lt. Kelsey) and one hit in the left wing (Lt, Westbrook). Lt. Joseph D. Winn, a 457th squadron pilot was listed as missing, (NOTE: Lt. Edwin Warfield was rescued by the submarine USS Haddock and was taken back to Pearl Harbor before he could be returned to the 506th Group. He later became Adjutant General for the State of Maryland, attaining the rank of Major General. He is now deceased.)If the sweep against the Tokyo targets was "pure, unadulterated rhubarb," the flight back to Iwo Jima was pure, unadulterated aerial frenzy. After forming up with our B-29 escorts at the rendezvous or rally point (RP), we headed south. Within less than an hour, we were deep into a weather front with thunderheads estimated to reach 30,000 feet. We continued to fly into this foul mess for another half-hour or so until, due to the close formations of the Mustangs and their "mother" B-29s, it became obvious we could not fly through it. So, the B-29 navigators made the decision to change course and attempt to fly around the storm. No doubt, this decision was influenced by a major disaster which resulted from a similar encounter with adverse weather on June 1.

Targeted Japanese airfields and environs |

On that fateful day, some 144 or more P-51s from the three Iwo Jima groups had taken to the air. Flying at 10,000 feet about 370 miles north of Iwo they ran into a weather front, the likes of which one might encounter only in the Western Pacific. Perceived to be a far greater enemy than the Japanese air force, this storm cost the lives of 24 pilots and the loss of at least 27 aircraft. Not counting some which had aborted the mission and returned to home base earlier, fewer than 100 Mustangs made it back home. Only about 27 of the 144 Mustangs launched from Iwo Jima on that day got through the storm and flew on to Honshu to complete the mission.

As we attempted to avoid the storm on July 28, we finally found our way around the storm and headed once again for Iwo. The official record says we landed at 1641 hours, a total flight time of eight hours and 12 minutes. Notwithstanding the mission summary, this pilot's AF Form 5 (flight record) reflects a flight time of eight hours and 45 minutes. It may not be in the Guinness Book of Records, but it surely approaches being the longest combat flight recorded by any fighter aircraft in World War II.

There is an interesting footnote to this account. Flight Officer Lon M. "Joe" Todd of Rome, GA, had become separated from the main body of aircraft either during the ground strikes over Japan or when we were scrambling around to get out of the storm. When I discovered he was missing, I thought, Poor Joe. He'll be down in the 'drink'! I prayed he would be rescued. But, to my surprise, when we arrived hack at Iwo Jima, there waiting alongside his Mustang to welcome us home was none other than Joe Todd. Joe said that after being separated from the flight, he could think of nothing better than to keep the heading on our charts. By dead reckoning, he had achieved the near impossible. He had found Iwo Jima as if guided by the hand of God. Why not?

The 506th Fighter Group arrived on Iwo Jima on May 11, 1945. Until war's end, August 15, 1945, the Group logged eight short-range missions, all against the Bonin Islands, and 25 very-long-range (VLR) missions. Six of the VLR missions were for B-29 escort. Nineteen were for sweeps, seeking targets of opportunity, ground attacks on airfields and other strategic targets and/or to fly top cover for other fighters on the attack.

2nd Lieutenant Edwin Warfield III, 458 Squadron

The 26th day of July 1945 was just another day as I climbed away from Iwo Jima in tight formation as one of a squadron of 16 single seat P-51 Mustang fighters headed for the heart of the Japanese Empire on a strafing run during the closing days of World War II. Heavy with fuel, we loosened up our tight formation and settled down for a long 3 hour, 600 mile, over-water flight, that would take us to Tokyo or if we didn't get lost in bad weather or the engine didn't quit before we got there. Since navigation equipment was sparse in a single seat fighter, we depended on a B-29 bomber to guide us to Japan and to circle off shore and bring us home.

The weather was perfect, the sky was blue, the Pacific one big mill pond. The Packard engine gave forth its noisy whine and, for the time being, there were no cares in the life of this 21 year old Iwo fighter pilot. Twenty feet to my left floated my Irish flight leader,Carmody, excellent pilot, older than the rest of us, who led us in the States. Now the squadron was on its 18th very long range mission out of Iwo-Jima, striving the heart of the Japanese homeland from 20 feet at 400 miles per hour, helping to finish the job Gen. Mitchell and his B-25's started.

On this particular mission, our flight of four Mustangs was designated Yellow flight, led by Carmody, with myself as second ship, Craig and Todd tucked in as three and four. Slumped down in the tiny cockpit, six feet tall, elbows against the sides, parachute strapped to the back like a pine board, the sharp gun sight reflector glass inches from your forehead,* ready to slice you in a rough landing, two slim wings holding you up, a mass of gages, this was a fighter pilot's war—lonely, boring and at intervals, exciting.Tacked under the windshield and over the dash, was an infantry canteen, full of water. It helped to overcome dehydration during the eight hour flights. I was to need it before this day was over. Three hours of over-water flight brought us to the coast of the long peninsula that stretches from Mito to on the north to the southern extremity of Tokyo Bay. Norwich leading the squadron, came up on the radio "Close it up - drop your tanks" our spare belly tanks useless and empty after the long trip North. Puffs of white smoke flared oat of all wings as pilots test fired their six fifty caliber guns. The squadron headed inland, north towards Mito. Blue and Green flights hit the deck and started strafing rail yards. We stayed high with Red and Yellow flights as top cover. The sweep headed south. At Isbioka, the strafing flights worked over a freight yard, factories and locomotives with noisy results. Johnson blew up a locomotive, Kelsey burned two box cars, the rest of the flight did likewise. Our turn came as Red and Yellow flights hit the deck. We swept down a rail line wide open shooting up a train. Slightly to the left. I swept over a farm house at thirty feet, caught a glimpse of a mother grabbing her children and dashing across a yard, swept over some trees at zero feet and arrived in the middle of an airfield loaded with flak.

I blasted a row of parked aircraft and was met with a hail of anti-aircraft fire from all sides. After shooting up the control tower, I made a hasty exodus, and was skimming over the edge of the airfield when my Mustang received a terrific thump in the nose section. It became dark, the wind screen was covered with oil. In a state of panic, I pulled back on the control stick to gain some altitude, the prop ran away, the engine over speeded. I dumped the bubble canopy and prepared to jump. I was delayed by a split second vision of our intelligence officer's briefing that in 1945 the Japanese people had declared open season on Yankee fighter pilots jumping out over Japan. The farmers greet you with pitchforks when you land. If you have to Jump out, try to make the American rescue sub surfaced near Tokyo Bay. The engine still ran, erratically, so I decided to nurse it along to the coast, 10 miles left of course, then hunt up a friendly sub and bail out and join up with the Navy.

Hot oil came over the windscreen. It covered my face and my goggles. I wiped it away. My flying suit flapped in the breeze—I had no canopy. The oil pressure was zero, the prop flailed away at full bore. The prop governor had packed up and quit. One thing at a time, I was still flying, limping along, called the rest of the flight for an escort to the lifeguard sub: no answer - the radio was shot out. I was running out of ideas. I couldn't find the sub, no radio, no friendly fighters, no escort bomber: short of fuel, the fighters were on their way home.

I had two choices, to jump out over Japan and be taken prisoner or worse, or start a 600 mile trip over water in a badly damaged Mustang. The homing instinct prevailed and I headed south. I did not intend to be taken prisoner even if it meant 600 miles of dead reckoning, with no radio, no navigation aids and no canopy, to hit a tiny island in mid-Pacific. Something told me to try it, so try it, I did. Heading southward towards Iwo, I climbed upwards through 6000 feet over the coast, past a layer of clouds, leveling at 10,000 feet, engine backfiring and oozing oil at every bore. After fifty minutes and 200 miles, I dared to hope that I could make it all the way to Iwo Jima and Just as I dared to hope the engine quit. Down we started with nothing below but the Pacific deep.

The next decision was easy, jump out. No pilot in his right mind ditched a Mustang. The pregnant bellied air scoop usually cocked it straight down as soon as it hit the water. I had a life vest, and I was hooked to a one-man raft as a seat cushion. Before I bailed out, I would drink the canteen of water. It was a waste to let it go down with the plane, and even if I wasn't thirsty I would be. I drank it in twenty seconds flat, and according to briefings, rolled the Mustang inverted with every intention of releasing my seat belt and falling free. Dirt, maps and debris fell in my face, and it seemed a poor way to jump out of an airplane so I rolled it right side up and jumped over the side. Knees tucked under my chin, I swept under the tail and missed it while doing violent somersaults. The chute opened, giving a temporary feeling of solid, serene security. I drifted through the layer of clouds. The ocean came up. Loaded with a pistol, G. I. boots, a survival vest, a Mae West life preserver and a deflated raft, my buoyancy seemed nill. My Mae West life jacket finally brought my head above water - with lungs bursting and swallowing large amounts of salt water. My chute floated. I released it and pulled the lanyard that inflated my fighter pilot's dinghy. It popped open and I crawled in, exhausted, sick and retching from the mixture of engine oil and sea water, but very much alive.

The time was 4pm, 28 July 1945.

Some B-29's flew over on a night strike, heading North flying low. I lit survival flares, put out a package of yellow sea dye marker and fired .45 caliber tracers to no avail. The bomber pilots had their own problems. So much for that. I took stock—healthy, alive, a twenty-one year old Maryland farm boy, never much for boating! I could swim.

I dug into the raft and survival vest and found a sea anchor, which was a plastic funnel hooked to a cord. I put it out, and the raft hove to and bobbed neatly into and over the waves. A cup to bail with. I tied it to the raft so that I would not lose it. A tiny blacksmith bellows device to keep the raft pumped up. I used it every two hours for the next four days. A book in my survival vest - "How to live in the jungle - eat roots and watch what Monkey's eat." I threw it overboard. My G. I. boots rubbed the skin of the raft. I threw them overboard. I saved my chute to cover myself with. I found sunburn salve and used it. Four bars of concentrated candy - 4 tin cans of water. I resolve to ration myself and decided that I could make it for ten days with a little fortitude and lot of luck. An intuition kept coming to me. You can make it. You will make it. I don't know how, but I will be saved. The feeling was there constantly. A lone fighter pilot in mid-Pacific — 200 miles south of Japan — with no one who had seen me bail out to organize a search. Yet, the inner message to stick it out was compelling.

Night fell and I dosed. I was wet. I was cold. I lost track of time.

29 July - A sunny dawn broke. I baled. I rested and slept. Some small bites of the candy bar two or three times a day, violent hunger cramps all day. Then appetite seemed to fade and cause no problem. The raft vas tiny, the sun was hot and my face and shins got sun burned. One more night. The sea got rough. It got choppy. The raft rose and fell like a cork, as the Pacific churned into a storm. The sea anchor held the raft true. It would ride that crest - drop in the trough, very rough but stable with no tendency to overturn. No sign of rescue. A plane engine in the distance — the 29th ended.

30 July — the third day dawned. The storm abated, the ocean calmed— no sign of rescue. A shark passed at the raft, flipped under it sideways and tapped it with his tail, I was transfixed, so did nothing and he left. An ugly fish with bulging eyes flipped by I grabbed it with my bare hands — looked at — could not bring myself to eat it. Threw it away. No sign of rescue — no hope of rescue, the 3rd day passed - no aircraft sighted. A fitful night.

31 July - The fourth day dawned. I was wet, tired, less confident. Toward mid-afternoon, a hum-a buzz-a roar. A Navy B-24 patrol plane approached on the Western horizon. I had no flares remaining. Just a small signal mirror. 1 focused it on the setting sun and pointed it toward the plane. It banked, turned and flew directly over me. A crewman waved out the back hatch—I cheered - I saluted - I waved. They dropped me an eleven man raft. It seemed as big as a dance floor. I paddled to it, pulled the cord to inflate it and got in it. I knew I was saved. I felt that if I could spend four days in a one man raft, I could spend thirty days in this larger raft.

Discretion being the better part of valor, I tied my trusty little raft alongside, in case the big one sank, my Navy friends meanwhile circled for an hour. They dropped a Gibson Girl signal radio, a kite to send up the aerial; a kit to turn salt water into fresh. I was as elated as a kid at Christmas as I experimented with all of the Air Sea Rescue devices. In a time-honored signal, the Navy pilot rocked his wings and headed South. He had called his patrol mate to circle me while he returned - low on fuel. The second patrol plane arrived on the scene and made lazy circles. He called up the U. S. Navy sub Haddock which arrived from seemingly nowhere. Unbeknownst to me, it had been in radio contact with the Navy Patrol Planes and Commander Stroud and the wonderful crew of the Navy sub Haddock took aboard a wet, tired and happy Mustang fighter pilot who joined the Air Force to fly and not to sail around in the mid-Pacific in a one man dinghy.

(1)Fighter Notes Sunsetters VII Fighter Command, AFF - Secret Vol 1. No.2 August 1945

(2) 506th fighter Group (S.E) Declassified Historical Division AAFPOA Microfilm.

Visitor:

Arrival time: 2/28/2026 at: 5:01:20 PM

Home | Reunions | Contact Us | VLR Story | Mustangs of Iwo Jima | Combat Camera Footage | Battle of Iwo | 457th | Webmaster ©506thFighterGroup.org. All Rights Reserved. |

©506thFighterGroup.org. All Rights Reserved.